Advocacy and Ambition Part 2

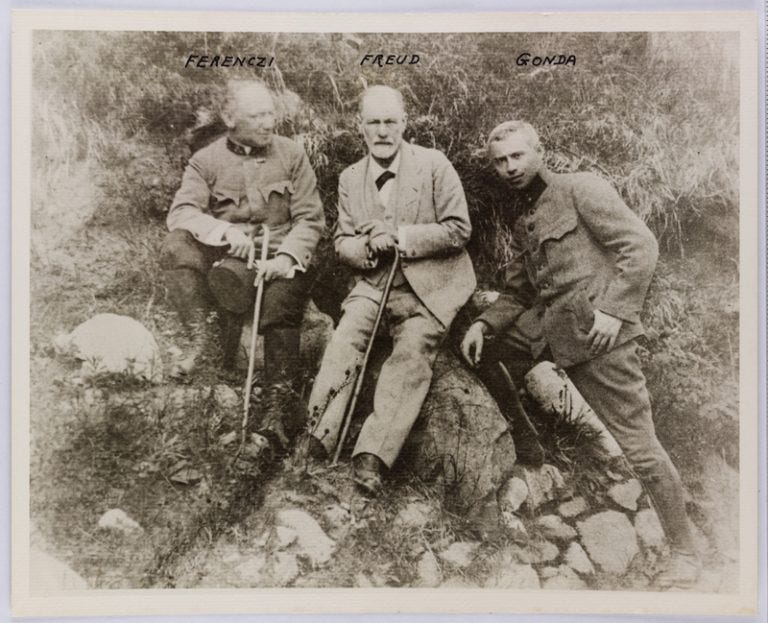

Sándor Ferenczi (left) with Sigmund Freud (middle) and Victor Gonda (right) in 1917, courtesy of the Freud Museum in London.

Last week I laid some groundwork for exploring why Freud went from believing sexual abuse victims to not believing them. Here in Part 2, I show more specific details of what was going on for Freud and two illustrative relationships related to this shift. I apologize for the length of this piece, but I didn’t want to draw it out into 3 parts! Quotes from Jeffrey Masson’s The Assault on Truth: Freud’s Suppression of the Seduction Theory are given in parenthesis.

Freud: Science vs Gullibility

Looking back on his initial seduction theory (again, that hysteria, aka dissociative trauma disorders, are caused by childhood sexual abuse) twenty-nine years later, Freud wrote,

“I believed these stories [of childhood sexual abuse]…If the reader feels inclined to shake his head at my credulity, I cannot altogether blame him…I was at last obliged to recognize that these scenes of seduction [ie sexual abuse] had never taken place, and that they were only fantasies which my patients had made up” (Masson, 11).

Why did Freud change his mind? Before moving on, it might be helpful to note that Freud was well aware of the likely criticisms that would come from his 1896 seduction theory paper. He acknowledged this in his closing remarks:

“I have now come to the end of what I have to say to-day. Prepared as I am to meet with contradiction and disbelief, I should like to say one thing more in support of my position. Whatever you may think about the conclusions I have come to, I must ask you not to regard them as the fruit of idle speculation. They are based on a laborious individual examination of patients which has in most cases taken up a hundred or more hours of work” (Masson, 289).

In 1925 Freud expressed sympathy for those who might shake their heads at his “credulity” (which here I believe is synonymous with gullibility). But in 1896 he clearly did not believe he was gullible, certainly not guilty of “idle speculation.” So what happened? In a letter to his best friend Wilhelm Fleiss dated September 21, 1897, Freud gives the following explanations for why “I no longer believe in my neurotica [ie, seduction theory]” (from Masson pp. 108-109):

-

The theory didn’t lead to successful treatment1: “The continual disappointment in my efforts to bring an analysis [ie treatment] to a real conclusion; the running away of people who for a period of time had been most gripped [by analysis]; the absence of the complete success on which I had counted.”

-

The theory became unthinkable: “Then the surprise that in all cases, the father, not excluding my own, had to be accused of being perverse—the realization of the unexpected frequency of hysteria, with precisely the same conditions prevailing in each, whereas surely such widespread perversions against children are not very probable.”

-

The theory is impossible to prove: “the certain insight that there are no indications of reality in the unconscious, so that one cannot distinguish between truth and fiction that has been cathected with affect [ie brought to conscious emotional awareness].”

-

Lastly and obscurely stated: “the consideration that in the most deep-reaching psychosis the unconscious memory does not break through, so that the secret [ie truth?] of the childhood experiences is not disclosed even in the most confused delirium.”

Freud goes on to write, “I was ready to give up two things: the complete resolution of a neurosis and the certain knowledge of its etiology in childhood. Now I have no idea of where I stand…” However, Freud boldly proclaims to Fliess that his doubt is not to be confused as weakness:

“If I were depressed, confused, exhausted, such doubts would surely have to be interpreted as signs of weakness. Since I am in an opposite state, I must recognize them as the result of honest and vigorous intellectual work and must be proud that after going so deep I am still capable of such criticism. Can it be that this doubt merely represents an episode in the advance toward further insight? It is strange, too, that no feelings of shame appeared, for which, after all, there could well be occasion…I could indeed feel quite discontent. The expectation of eternal fame was so beautiful, as was that of certain wealth, complete independence, travels, and lifting the children above severe worries which robbed me of my youth. Everything depended upon whether or not [his theory of] hysteria would come out right. Now I can once again remain quiet and modest, go on worrying and saving” (Masson, 109).

It’s hard to avoid interpreting, in good Freudian fashion, the pride and ego shown in this self-analysis. Here he admits to the self-serving ambition that motivated his interest in studying hysteria: fame, wealth, a truly bourgeois lifestyle.

But there’s a certain irony in disclaiming ego and instead claiming to be humble in giving up his theory that sexual traumas cause hysteria. It seems that the opposite was the case: by giving up his bold theory he avoided the humiliation that maintaining it would have caused. Instead, he kept his ego intact, maintained relationships threatened by his theory, and in the end acquired the “eternal fame” he desired all along.

For, according to Masson, all historians of the psychoanalytic movement agree that psychoanalysis, and indeed all of modern psychology, owed its popular success to Freud’s disavowal of his seduction theory. By assigning his patients’ troubles to the work of fantasy, instead of objective traumas, he unlocked key theoretical and practical insights into the working of the unconscious. All of the Freudian terms you are no doubt familiar with stem from this shift from objective trauma to subjective fantasy: defense mechanisms, denial, the id/ego/superego construct, the Oedipus complex, transference and countertransference in the therapy relationship, etc.

But I’m getting off topic here. I am less interested with Freud’s theory itself, and more interested in his decision to change his mind and stop believing reports of childhood sexual abuse. Two more aspects of this history deserve mention here. First, involving Freud’s relationship with Fliess, and then his later relationship with another close friend and disciple Sándor Ferenczi.

Wilhelm Fliess

As mentioned in Part 1, much of Masson’s explanation of Freud’s change of mind is based on private correspondence with Wilhelm Fliess that was omitted from publication. Masson suggests multiple reasons why Fliess likely did not support Freud’s early theory. Tragically and ironically, one suggestion is that Fliess himself was sexually abusing his son Robert Fliess during the very time Freud was developing his theory on the cause of hysteria. The evidence Masson gives in his book for Robert’s abuse by his father seems more open to debate than the rest of Masson’s research. But the evidence he gives is suggestive, and certainly believable in theory (see Masson pp. 138-142). Confirming this evidence, Masson shared in a 2019 interview that he got to know Robert Fliess’ widow after his death, and she told Masson, “There is no question, he believed he had been sexually abused by his father.”

If true, Fliess couldn’t take Freud’s theory seriously because, at the very time Freud was gathering and analyzing data from his patients, Fliess himself was guilty of the crime Freud was researching. This reminds me of a recent case2 in the Presbyterian Church in America where a committee of the Nashville presbytery was looking into spiritual abuse allegations against Scott Sauls. The man chairing that committee, Ian Sears, was himself credibly accused by multiple women of sexual abuse. Although I know nothing about Sauls’ personal relationship with Sears, the irony is similar:

“Freud is communicating his newly gained insights to the one person least prepared to hear them, because of the profound significance these theories held for that person’s own life. Freud was like a dogged detective, on the track of a great crime, communicating his hunches and approximations and at last his final discovery to his best friend, who may have been in fact the criminal” (Masson, 142).

While there is no evidence that Freud was aware of Fliess’ potential abusive behavior, one wonders if the friendship blinded Freud to what he may have otherwise been able to spot. Regardless, it is part of an overall convincing picture that Freud could not and would not have maintained his friendship with Fliess so long as he maintained the belief that hysteria was caused by real sexual violence. Indeed, Freud himself later disowned his mentee-friend Ferenczi for that very reason.

Sándor Ferenczi

In September 1932 Sándor Ferenczi (1873-1933) presented a lecture titled “Confusion of Tongues between Adults and the Child: The Language of Tenderness and of Passion.” The connection he draws between neuroses (ie mental illness) and sexual trauma is almost a carbon copy of Freud’s 1896 paper on the cause of hysteria. But unlike Freud, Ferenczi reads like a modern-day compassionate discussion of the nature and treatment of sexual trauma.3 Ferenczi was himself guilty of serious boundary violations with patients, but consider this contrast between traditional psychoanalysis and his corrective proposal, which, he believed, could facilitate the retrieval of objective memories, that is, truthful reports of sexual trauma.

“The analytic situation, with its reserve and coldness, professional hypocrisy and the dislike of the patient it masks, which the patient could feel in his bones, was essentially no different from what had led to the illness in his childhood. Since in addition we urged the patient to reproduce his trauma in an analytic setting of this sort, we created an unbearable situation; no wonder that it could have no other and no better consequences than the original trauma itself. However, the setting free of [the patient’s] criticism [of the psychoanalyst], the capacity to recognize our mistakes and to avoid [and admit] them, bring us the patient’s trust. That trust is a certain something that establishes the contrast between the present [safe therapy relationship] and the unbearable, traumatogenic past, a contrast therefore which is indispensable to bringing the past to life, no longer as a hallucinatory reproduction, but as an objective memory” (Masson, 295).

While the reference to “objective memory” indirectly implied Ferenczi’s belief in the truthfulness of his patient’s stories, he was also quite explicit about his belief:

“Above all, my previously communicated assumption, that trauma, specifically sexual trauma, cannot be stressed enough as a pathogenic [ie causal] agent, was confirmed anew. Even children of respected, high-minded puritanical families fall victim to real rape much more frequently than one had dared to suspect” (Masson, 297).

It was this direct calling out of the problem of sexual abuse that the psychoanalytic community considered taboo and unacceptable. Ferenczi’s paper was met with criticism, albeit passive-aggressive. It was translated into English by Ernest Jones for publication in America in 1933. However, Ferenczi died on May 22, 1933, and Jones wrote to Freud less than 2 weeks later:

“It is about Ferenczi’s Congress paper [“Confusion of Tongues”] that I am now writing. Eitingon did not wish to allow it to be read at the Congress, but I persuaded him. I thought at the time of asking you about its publication in the Zeitschrift. I felt he would be offended if it were not translated into English and so asked his permission for this. He seemed gratified, and we have not only translated it but set it up in type as the first chapter in the July number [of the International Journal of Psycho-Analysis]. Since his death I have been thinking over the removal of the personal reasons for publishing it. Others have also suggested that it now be withdrawn, aand I quote the following passage from a letter of Mrs. [Joan] Riviere’s4 with which I quite agree: ‘Now that Ferenczi has died, I wonder whether you will not reconsider publishing his last paper. It seems to me it can only be damaging to him and a discredit, while now that he is no longer to be hurt by its not being published, no good purpose could be served by it. Its scientific contentions and its statements about analytic practice are just a tissue of delusions, which can only discredit psychoanalysis and give credit to its opponents [see the ideological war here?]. It cannot be supposed that all Journal readers will appreciate the mental condition of the writer, and in this respect one has to think of posterity too!’ I therefore think it best to withdraw the paper unless I hear from you that you have any wish to the contrary” (Masson, 152).

While there is no written record of Freud’s response, a letter from Jones to another psychoanalyst, A.A. Brill, on June 20, 1933 shows that Freud agreed:

“To please him [Ferenczi] I had already printed his Congress paper, which appeared in the Zeitshchrift, for the July number of the Journal, but now, after consultation with Freud, have decided not to publish it. It would certainly not have done his reputation any good” (Masson, 153).

Brill’s response on August 11, 1933 says it all (emphasis added):

“I fully agree with you about the publication of his paper. The less said about this whole matter, the better.”

Better for whom, Mr. Brill? Victims of childhood sexual abuse? Ferenczi? Or for Frued and his disciples? As Masson observes, “the lack of loyalty toward a former friend and the rapid move to strangle ideas contrary to accepted doctrine are distressing” (Masson, 153).

Ferenczi was clearly distressed by the obvious lack of loyalty. On October 10, 1932 he wrote this in his private journal (emphasis added):

“I have just this minute received a friendly personal letter from Jones [presumably about publishing his paper, which he didn’t know was disgenuous] . . . . I cannot deny that even this pleased me. For I felt abandoned by my colleagues . . . , all of whom had too much fear of Freud to be objective in a dispute between Freud and me or even to show me any personal sympathy” (Masson, 188).

Lessons Learned

As

ann maree recently put it at Help[H]er Substack , sometimes favors have an expiration date. The parallels with the story of Freud’s change of mind are striking. When reading Dr. Goudzwaard’s post, I imagined something like a restaurant gift card that would expire if not used by 12/31/2024. The problem, though, is the one giving the favor gets to decide the expiration date (usually without advance notice). And they get to decide what it is specifically that leaves you having to scrounge for loose change in your car after finishing an expensive steak dinner you thought was paid for. But while the specific what can be hard to anticipate, the general what is clear from Ann Maree’s story, from Ferenczi’s story, from Masson’s story, from my wife’s story: toe the party line, you can wine and dine; but step out of line, you get the silence of a mime, from those you thought friends and mentors.

Advocacy and ambition do not mix. Ambition is rot in the foundation of care for victims, survivors, and those in crisis in the church. Like oil and vinegar, you can shake them up to put on a salad (or submarine sandwich, which I’m ambivalent about), but the temporary and artificially joined substance doesn’t have any healing properties. While vinegar was used medicinally since ancient Greece, oil and vinegar is a dressing for food, not a bandage to dress a wound. One can claim all day that oil and vinegar cleans wounds, make commercials and informercials for that claim, manufacture in bulk at a warehouse, hire drug reps and give free samples to doctor’s offices, but at the end of the day, all of the advocacy is overpowered by the ambition. Survivors and caregivers might get some help in a roundabout way—like staff and patients at a doctor’s office getting free food paid for by Pfizer—but it’s still just food that fills the belly, leaves the next day (or sooner, as I recall from the typically greasy meals I had when I managed a medical office), and doesn’t do anything to cure the illness.

Quote from Jeffrey Masson

“I am inclined to accept the views of many recent authors, Florence Rush, Alice Miller, Judith Herman, and Louise Armstrong, among others, that the incidence of sexual violence in the early lives of children is much higher than generally acknowledged…But whether it is openly stated or merely accepted as a hidden theoretical premise [ie presupposition], the analyst who sees such a patient is trained to believe that her memories are fantasies. As such, the analyst, no matter how benevolent otherwise, does violence to the inner life of his patient and is in covert collusion with what made her ill in the first place” (191).

1 Ferenczi’s development of Freud’s seduction theory into a more empathic, compassionate, interpersonally grounded therapy shows that the problem was with Freud’s therapy approach, not the etiological theory itself. Ferenczi had his own problems, but being a cold, detached therapist wasn’t one of them.

2 The Tennessean articles are paywalled. If you’re on Twitter/X, you can read portions from reporter Liam Adams here: https://x.com/liamsadams/status/1707386567872991467.

3 See Masson’s translation, Appendix C in The Assault on Truth.

4 It is noteworthy that one of Ferenczi’s objectors was a woman. Joan Riviere was an influential British psychoanalyst, who after being analyzed by Ernest Jones became closely connected with the Freudian school of psychoanalysis, especially as a translator of Freud’s works. This suggests she too stood much too gain or lose by maintaining ties to Freud and protecting Freud’s theories.