Marie Dentière: A late addition to Calvin’s critics

Reformation wall in Geneva (1909), where Marie Dentière is the only woman named, added in 2002.

This is part five in a series considering the claim that John Calvin was a tyrant. If you are just joining this journey, I encourage you to check out part 1, part 2, part 3, and part 4. Also, while all of these posts have been long, this one is even longer. It seemed appropriate to devote extra time and space to an under-studied Reformation figure. Remember you can listen to my voiceover on 2x speed!

On Reformation Day, 2023, I posted a meditation on John 20 and the reforming message of Mary Magdalene’s witness to the absent body of Jesus. How fitting and providential is it that just before Reformation Day, 2024, through absolutely no planning on my part, I studied the story of another Mary who was herself inspired by the Magdalene to proclaim the risen Jesus and bear witness to where his absence was felt in her day.

Shout out to

Anna Anderson for reminding me about Marie Dentière (1495-1561). If you’re unfamiliar with many of the figures studied in this series, it’s all the more likely that you’ve never heard of Dentière.1 I regret my participation in the male bias that perpetuates occlusion of female theologians, for I am only telling you about Dentière after highlighting eight male Protestants, and only because another woman brought her to my attention.

I’m doubly grateful to Anna for the timing, because 1) Dentière deserves a full post; 2) I just happened to have this ready before October 31; and 3) fitting her into this series on Calvin will require some nuance and detail. There is much to be gleaned from Dentière’s life and writings, especially vis à vis women in the church. I want to touch on that somewhat, but the focus of this series is perceptions of Calvin’s tyranny by his contemporaries.

Marie Dentière (1535-?)

As mentioned in Part 3, the first date above is the rough beginning of a relationship with / connection to Calvin, and the second date is an approximation of when that favorable connection was severed. As we’ll see, the historical record is unclear on Dentière’s relationship with Calvin/Calvinism over time.

Dentière, born in Flanders in 1495, was an Augustinian nun who left her order to join the reformation in the 1520s. She married an ex-Catholic priest, Simon Robert, and moved to Strasbourg in 1525 where they were both ministered alongside Farel and the early French-speaking reformation. Robert died in 1533 and left Dentière with three children. Sometime after that Dentière remarried Antoine Froment (1509–1581), another reformed pastor and mentee of Farel. They followed Farel to Geneva in 1535 to participate in the reformed evangelical movement there.2

Dentière’s strong commitment to the reformation is evidenced in her impassioned plea to Marguerite of Navarre for support when Geneva expelled Calvin and Farel in 1538. Written to Marguerite in 1539 and published later that year as a Very Useful Epistle, it is more than just a letter. According to McKinley, Dentière’s use of style, rhetoric, and language fits with the sermon tradition of Farel.3 The sermonic quality of the Epistle fits with its message, which includes a bold biblical argument for women preachers and teachers. We’ll return to consider the Epistle in a bit.

“A Humorous Story”

One of the few times Dentière appears on the scene after 1539 is in a dirisive letter from Calvin to Farel dated September 1, 1546. Calvin relates a debate between himself and “the wife of Froment” regarding what Scripture teaches about ministerial attire. Because of the occurrence of the word tyranny (see below), I read this in Letters of John Calvin in my earlier study for this series, but I didn’t know the “wife of Froment” was Marie Dentière. For those interested, you can read the whole letter here (just do a word search for “Froment”).

According to Calvin, who mockingly opens his account to Farel with “I am now going to give you a humorous story,” Dentière was engaging in public preaching in Geneva:

“The wife of Froment lately came to this place. She declaimed through all the shops, and at almost all the cross-roads, against long garments.”

The first question that occurs to me is not, why was she “declaim[ing] against long garments,” but why was she preaching in Geneva in the first place? Before getting to that question, however, here is a comment from Irena Backus about the “long garments”:

“Unfortunately there is no record of the sort of robe that Marie advocated for pastors in place of the long black one that was standard wear in the Genevan church. Calvin goes on to say that he argued with Marie and rebuked her sharply when she said that the pastors were comparable to the Jewish scribes in Luke 20:45 who wanted to flaunt their office by walking about in long garments. We can surmise from this that Marie found the clerical garment exaggerated and that she would have preferred something less conspicuous and less intrinsically “male” by way of a pastoral robe, a view shared by the radical reformers of the time.”4

So that may explain Dentière’s specific criticism, at least as recounted by Calvin. Although, given his depiction of her preaching “through all the shops, and at almost all the cross-roads,” I seriously doubt her message was limited to criticizing ministers’ robes.

But why was she in Geneva at all, when she and her husband lived elsewhere?

We don’t know much at all about Dentière’s actions aside from a few third-person accounts, but we can track her with her husband’s career. Though you likely have also not heard of Antoine Froment, he was a leading figure in the early attempts at reformation in Geneva before Calvin. He preached the first reformed sermon in Geneva in 1533, pictured below.

Froment preaching in Molard Square, Geneva, by Auguste Viande (1825-1887)

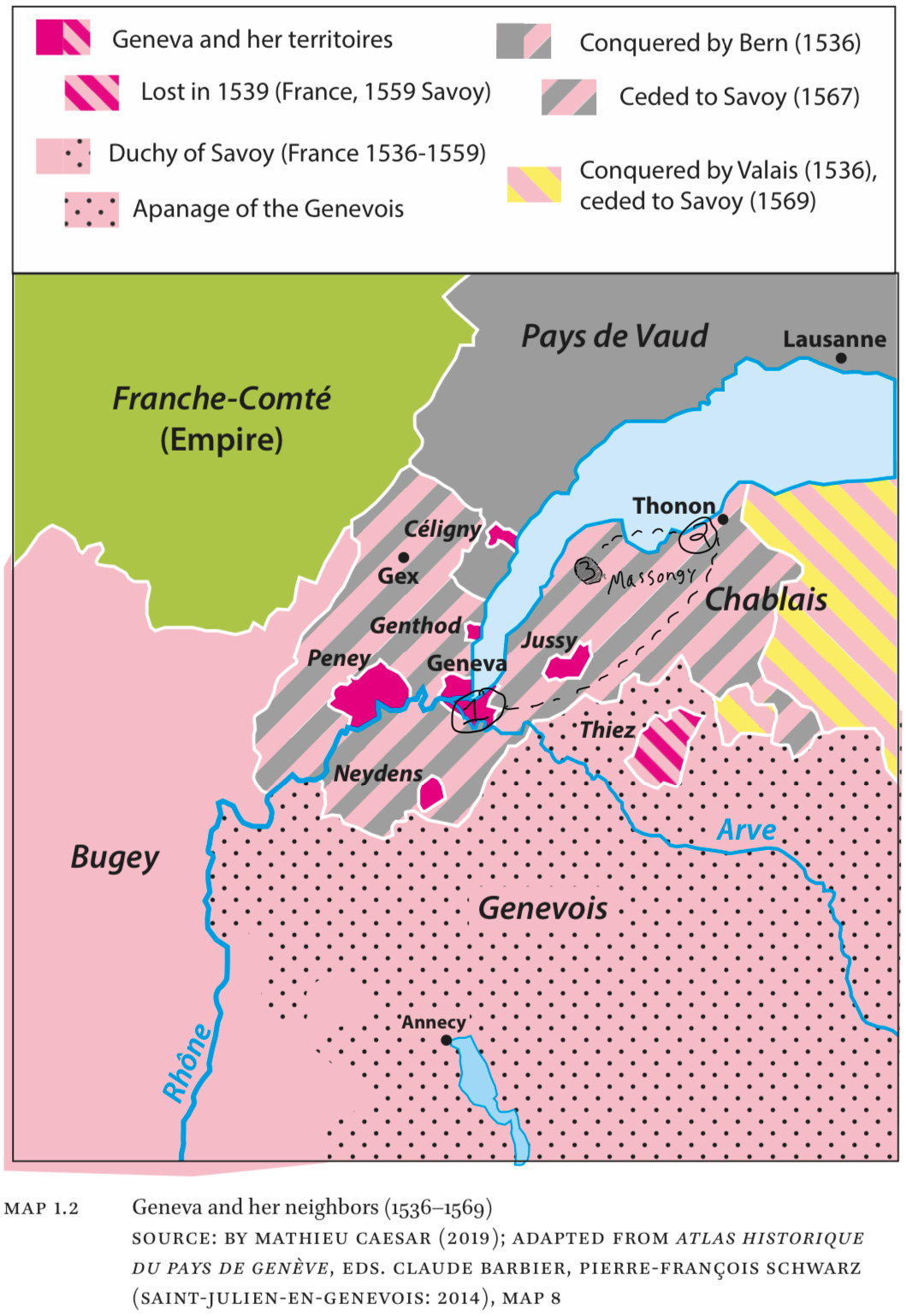

When Dentière and Froment moved to Geneva in 1535 he opened a school to teach young children French. In 1537, he was pastor of Saint-Gervais in Geneva and then appointed deacon later that year in Thonon in the Chablais, on the south shore of Lake Geneva.5 As indicated by the Very Useful Epistle (1539), Froment and Dentière kept up with what was going on in Geneva, even though Thonon was under the jurisdiction of Berne, a neighboring canton in the Swiss Confederation. Froment took a pastoral post at Massogny in 1540, which is between Geneva and Thonon and also Bernese.6

You can see the cities in which Dentière and Froment lived during this period on the map below7: Geneva, Thonon, and Massongy.

Froment remained pastor at Massongy until 1548, when the Berne Council removed Froment after he “preached a sermon attacking the church leaders of Germany, Constance, Berne, and Geneva, accusing them of making private gain from their ministries and losing sight of the spirit of the Reformed Church.”8

Reforming the Reformed

So, what was Dentière doing in Geneva in 1546? Froment’s preaching in 1548 seems suggestive; perhaps they were like-minded in criticizing other reformed leaders. During this time Froment was the pastor of a Reformed church in a Bernese city, and Bern was in constant negotiations and doctrinal debates with Geneva throughout the 16th century. This is pure speculation, but Bruening’s studies of the conflicts between Calvin/Geneva and the other territories surrounding Lake Geneva (the Pays de Vaud and the Chablais) make me wonder if Froment and Dentière came to see in Geneva what many other leaders in those areas saw:

“Many [in the Pays de Vauds] also resented what they saw as Calvin’s self-appointed leadership of the francophone Reformed Churches in the region. They labelled him the “pope of Geneva” and called the trio he formed with Viret and Farel the “three patriarchs.” Far from supporting the Reformed ideal of the equality of ministers, Calvin, they thought, had set up a hierarchy of individual leaders and cities, with himself and Geneva at the top.”9

Speculating further, what other significant events happened in 1546? Might these provide any context for Dentière’s prophetic preaching in reformed Geneva? One scenario stands out, involving a character studied in Part 4: Henri de la Mare.

On April 15, 1546, Henri de la Mare was ousted from his pastorate due to his support of Pierre Ameaux and for criticizing Calvin. De la Mare was the pastor of Jussy, a rural Genevan church nearby to Massongy where Froment pastored. Surely Froment, Dentière, and de la Mare knew each other. It’s hard to imagine the couple being unaware of de la Mare’s firing, if not also his ongoing mistreatment by Calvin. According to Naphy,

“De la Mare made one final appearance in the city records in June 1546 when he requested that he be compensated for the repairs which he had been forced to make on his house. He also asked for a letter of attestation so that he could accept a post on the Bernese territory of Gex; both requests were granted. He later used his pulpit in Gex to thunder against Calvin, personally and theologically. After six years of facing Calvin’s opposition he was to remain a problem for Calvin for a few more years.”10

While the Pays de Gex is to the northwest of Geneva, on the other side of the lake from Massongy, for de la Mare and many other ex-Genevan ministers, Bern provided a place of exile in which Calvin’s former friends and allies networked around their animosity toward Calvin. In fact, Antoine Marcourt, the former Genevan pastor during Calvin and Farel’s exile from Geneva, ministered in Gex after Calvin returned to Geneva, and he “frequently opposed the positions taken by the Calvinists inside the city.”11 Bruening notes many such anti-Calvinist hubs in Bernese territory, including Veigy in the Chablais, which is between Jussy and Massongy. Veigy was the home of Seigneur Jacques de Falais, the nobleman and former friend of Calvin mentioned in Part 4 of this series. Although post-dating the Dentière-Calvin encounter by a few years, the Falais “estate at Veigy would become a center of anti-Calvinist activity around Lake Geneva.”12

Still, this is speculation, and historians will probably question reading any of this into Dentière’s story. However, I thought this speculation worthwhile, because there must be some explanation for Dentière’s showdown with Calvin. Given the intelligence and reformed spirit demonstrated in the Epistle (see further below), it seems fair to Dentière to assume she took issue with more than just clothing. McKinley notes a line from the Very Useful Epistle attacking Catholic clergy in similar language: “They walk about in long robes and sheep’s clothing, but inside are ravishing wolves.”13

Unfortunately, however, we have no knowledge of what else Dentière may have said in her public preaching. We only have Calvin’s account, but he does tell us that Dentière “complained of our tyranny.” Here are slightly different translations from Bonnet (editor of Calvin’s letters in 1857) and from Reformation scholar Irena Backus:

“Feeling that she was closely pressed, she complained of our tyranny, because there was not a general license of prating about everything. I dealt with the woman as I should have done.” (Letters, 2:57)

“Feeling under pressure she complained about our tyranny, about how it was no longer permissible for people to speak their minds. I treated the wretched woman as I should have.” (Irena Backus)14

You’ll notice that in Bonnet’s translation, the first half sounds more belittling: “prating about everything,” vs “speak their minds.” In Backus’ translation, the final sentence brings out Calvin’s misogyny (“the wretched woman” vs “the woman”). In either case, I wonder, did Dentière actually use the word “tyranny”? Or is that Calvin’s way of making her complaint sound over the top and outlandish? We only have Calvin’s words to go on here, and he is not always a reliable historian.15 What seems clear is that Dentière believed she had the right to teach Scripture, to preach publicly against ministers whether Catholic or Reformed, and the right to defend her Scriptural interpretation and conduct. If she complained anything along the lines of “it was no longer permissible for people to speak their minds,” that very much fits complaints and descriptions of Calvin’s tyranny noted from other ex-Calvinists.

Frustratingly, it’s impossible to know how Calvin responded to that debate and Dentière’s criticism of tyranny. Here is the rest of his account:

“I dealt with the [wretched] woman as I should have done. She immediately proceeded to the widow of Michael [?], who gave her a hospitable reception, sharing with her not only her table, but her bed, because she [the widow?] maligned the ministers. I leave these wounds untouched, because they appear to me incurable until the Lord apply His hand.”16

Context from the Very Useful Epistle

If a male preacher preached as she did, Calvin would have pursued more severe consequences. Indeed, as we’ve seen time and time again, men who disagreed with Calvin were simply not welcome in Geneva. This may have included Dentière’s second husband Froment, who “did not share Calvin’s view of women’s role in the church,” as shown by him helping Dentière publish her Very Useful Epistle.17 Written in defense of Farel and Calvin during 1538-1541 when the opposing Articulant party was in power in Geneva, such pro-Farel/Calvin literature could not be tolerated. When the Geneva Council discovered the Epistle, they arrested the printer Jean Giarard and seized what copies remained in his shop. Froment appealed the Council to release the copies, but they refused and presumably destroyed them. “However, enough copies had already been circulated that the efforts to suppress the Epistle were only partly successful.”18

While the Council’s negative response to Dentière’s publication was more political, other reactions were more theological. Some doubted it was written by a woman, referring to it as “Froment’s book.” One pastor in Lausanne, a Bernese city, wrote,

“It is not against Holy Scripture, nor against our religion and faith. But it is true that it has certain articles that can be misinterpreted by the wicked and malicious, and that it is not appropriate for the current times. Furthermore, because the title announces that a woman (who has no business prophesying in the Church) dictated and composed it, and because that is not true—for that reason he advises suppressing the book and thinks it not worth a squabble. It is decided that at the same time the judgment be announced to Froment in a letter.”19

As McKinley explains, we learn about perceptions of Dentière through reactions to her husband. “While we cannot assume that the life of the husband always parallels that of the wife, contemporary reports of Froment’s activities imply that she was actively involved in his work and even an important influence on him—a bad influence, according to these reports.” For example, Farel wrote to Calvin six months prior to the Epistle’s publication: “You know how Froment, a very imprudent man who cares little about the church, behaves with his wife—unless it is she who makes him behave that way.” A year later, “Farel again complained about Dentière’s influence on her husband,” writing, “Our Froment, first in his home by following his wife’s example, has degenerated into a weed [a pun on “froment” which means wheat], and we would have expected nothing less of them, since they have such a bad reputation among the lovers of sects to whom they have been hostile.”20 (Here I am reminded of one South Carolina misogynist who, referencing my wife, said to me, “You better keep that woman on a leash.”)

Toward the end of her Very Useful Epistle, Dentière shifts from criticizing Catholic clergy to leveling similar acerbic charges against Reformed ministers: particularly, those in France who refused to make clear breaks with Rome, as well as those in Geneva who sided with the Articulants in expelling Calvin and Farel.21 It’s not clear who Dentière has specifically in mind with the following quote, but my guess is Catholics:

“It has come to the point that if anyone contradicts, preaches, or writes against them, he will quickly be judged a heretic, a seducer of the people, a founder of new sects.”22

Written in 1539, this sounds very similar to Calvin’s summary of Dentière’s response to him in 1546, “that she complained about our tyranny, about how it was no longer permissible for people to speak their minds.” This is also remarkably similar to the complaints we have heard from former friends and allies of Calvin. Indeed, she criticizes tyranny (and synonyms for sinful control) many times in the Epistle. If we read these statements, and then fast forward to 1546, we can imagine Dentière seeing the need to transfer these same criticisms to Calvin/Geneva. Here are just a few examples:

“What do you fear from the cardinals and bishops who are in your courts? If God is on your side, who will be against you? Why don’t you make them support their case publicly, before everybody? They are just so many doctors, so many wise men, so many great clerics, so many universities against us poor women, who are rejected and scorned by everyone. What good are they to you, I ask you, if they will not show that their cause is good, ordained by God? Will you put up with them and let them dominate you?” (61)

“For just as by hypocrisy and the force of tyranny that knowledge [of Scripture] was extinguished and suffocated for a time, so by the virtue and power of the sword of the spirit of God it will be illuminated and revealed, no matter what the tyrants do.” (65)

“They [Catholics] not only trick, seduce, and pillage the poor people, but, worse than Turks and infidels, like mad dogs, they have the enemy and adversary of God adored. They try by their tyrannies to make him be adored…You see it clearly enough in the way that those who would preach Jesus and his word purely are run out of the courts of kings, princes, and lords. But in abjuring and returning to kiss the slipper23 of that great locksmith [the pope], adversary of Jesus, they are given benefices, prebends, revenues, crowns, and mitres, and even worse, under the guise of the gospel.” (77-78; here we might also detect a precursor to Froment’s later preaching against ministerial greed)

Regarding this section of the Epistle, McKinley writes,

“Here and in the passage that follows, she defends the faith of the simple people, the kind of faith she attributes to women and to the reformed religion, against the tyranny of the Catholic theologians who claim authority to define doctrine from their privileged positions in the universities and in papal councils.” (80 n. 59)

Reading the Epistle in the context of the network of Calvin’s opponents in the Pays de Vaud, who leveled similar criticisms against Calvin, it becomes easier to imagine why Dentière would have “complained about [Calvin’s] tyranny, about how it was no longer permissible for people to speak their minds.” Situating the 1546 encounter Dentière and Calvin thus, McKinley’s comments are all the more convincing:

“Here we see an even more audacious Dentière than the woman who exhorted the Poor Clares [Catholic nuns] to leave their convent [in 1535]. Now she is determined to reach a wider, more public audience. She is once again reviling the ministers of Geneva, but now Calvin is their leader [compared to her Epistle which criticized the Articulant ministers]. Where Jeanne de Jussie [Catholic critic of Dentière] portrayed her as a comrade of Farel’s and Viret’s, here she is alone, alienated from the very people she had supported. But she remains undaunted. Seven years after writing her Epistle, she does not hesitate to challenge even Calvin…Eleven years later [after evangelizing the Poor Clares], she has become even bolder. She goes to the most public of urban spaces, a woman daring to preach in the taverns and on the street corners, places traditionally frequented by men. She is a woman unafraid to confront even Calvin, to criticize his behavior and accuse him and his associates of tyranny and error.”24

A Principled Protestant Woman

Dentière’s grasp of the Reformed spirit is truly inspiring. To be a woman in 16th century Europe and engage in public proclamation of Scripture to both men and women is remarkable. To engage Calvin in debate about the meaning and application of Scripture, as a woman, is remarkable.25 Dentière believed and practiced the “Protestant principle”:

“as explained by twentieth-century theologian Paul Tillich…the enduring legacy of the Reformation lay not in the doctrines of the Protestant reformers…but in the protest itself against existing religious institutions. ‘The Protestant principle,’ Tillich writes, ‘contains the divine and human protest against any absolute claim made for a relative reality, even if this claim is made by a Protestant church. The Protestant principle is the judge of every religion and cultural reality, including the religion and culture which calls itself Protestant.’ In other words, it is the need constantly to test, evaluate, and judge all human religious institutions.”26

The Protestant Principle includes principled attentiveness to the possibility and presence of tyrants. The enduring lesson for us in this series is the ways in which (alleged) tyrants and their institutions often marginalize their critics. I assume some will disagree with joining Marie Dentière to those who considered Calvin a tyrant (and some will also agree with the prevailing 16th century opinion “that a woman…has no business prophesying in the Church” or writing theological literature). Perhaps I have only amassed 4,000 words of speculation. But even there the lesson endures: I have only done this because we never hear Dentière’s complaint against Calvin in her own words.

Quote from Marie Dentière

“Not only for you, my Lady [Margeurite de Navarre], did I wish to write this letter, but also to give courage to other women detained in captivity, so that they might not fear being expelled from their homelands, away from their relatives and friends, as I was, for the word of God. And principally for the poor little women wanting to know and understand the truth, who do not know what path to take, what way to take, in order that from now on they be not internally tormented and afflicted, but rather that they be joyful, consoled, and led to follow the truth, which is the Gospel of Jesus Christ…For until now, scripture has been so hidden from them. No one dared to say a word about it, and it seemed that women should not read or hear anything in the holy scriptures. That is the main reason, my Lady, that has moved me to write to you, hoping in God that henceforth women will not be so scorned as in the past. For, from day to day, God changes the hearts of his people for the good. That is what I pray will soon happen throughout the land. Amen.”27

Question

Dear reader, what do you think of this post, of Marie Dentière, of this series? I would love to hear from you in the comments below.

1 Contemporary awareness of this reformer is owing to work by Mary McKinley, at the University of Virginia in the late ‘90s and early 2,000’s, culminating in a scholarly English translation of Dentière’s extant works in 2004; as well as Isabelle Graesslé, the first female moderator of the Geneva Company of Pastors and Deacons, who advocated for adding Dentière’s name to the Geneva Reformers Wall in 2002 (pictured above). See Jeff Persels, Kendall Tarte, and George Hoffmann, Itineraries in French Renaissance Literature: Essays for Mary B. McKinley (Leiden: Brill, 2017), 15-16; Marie Dentiere, Epistle to Marguerite de Navarre : And, Preface to a Sermon by John Calvin, translated by Mary McKinley (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2004); Isabelle Graesslé, "Reformation Sunday: Ecclesiastes 9:14–18a; 1 Ephesians 2: 4–9; John 8:12–14b", Semper Reformanda.

2 See McKinley, 2-5.

3 Merry Low, “Listening to the “Voix Prescheresse” in Marie Dentière’s Epistre tres utile,” _Women In French Studies Special Conference Issue (_2019), 57

4 Irena Backus, “Women around Calvin: Idelette de Bure and Marie Dentière,” in Stueckelberger, Christoph, and Bernhardt, Reinhold (eds.), Calvin Global: How Faith influences Societies (Geneva: Globethics.net, 2009), 108-109.

5 Backus, “Antoine Froment,” https://hls-dhs-dss.ch/fr/articles/011115/2007-06-05/. I’m not sure what source Backus used that placed Froment as the pastor of Saint-Gervais in Geneva in 1537. Naphy’s Consolidation provides a thorough list of all the Genevan pastors of that time, and it does not include Froment.

6 Backus, “Women around Calvin,” 108.

7 From Mathieu Caesar, “Government and Political Life during an Age of Transition (1451–1603),” in A Companion to the Reformation in Geneva, edited by Jon Balserak (Leiden: Brill, 2021), 34.

8 McKinley, 21. This is an ironic criticism, for pastoral colleagues in the Chablais complained to the Berne Council that “While in Geneva he was more a merchant than a preacher” (he and his wife ran a shop of some kind in Geneva), and that “he purchased a lot of oil in town and in the villages around Thonon and became an oil merchant…We consider him a real Demas, seeing how avidly he embracd the love of the world” (McKinley, 16-17).

9 Bruening, “The Pays de Vaud: First Frontier of the Genevan Reformation,” in A Companion to the Reformation in Geneva, edited by Jon Balserak (Leiden: Brill, 2021), 132.

10 Naphy, 67.

11 Bruening, “The Pays de Vaud,” 134.

12 Bruening, “The Pays de Vaud,” 136.

13 McKinley, 57.

14 Backus, “Women around Calvin,” 109. See Gordon, 143, who does not specify Dentière’s identity, and summarizes, “Although the fiesty [sic] woman was unwise to attempt to best Calvin in quoting scripture, she did manage to gall him by being warmly received by others on account of her abuse of the ministers.”

15 See Naphy, 57.

16 Letters of John Calvin, 2:57.

17 Backus, “Women around Calvin,” 108.

18 McKinley, 14.

19 McKinley, 15.

20 McKinley, 16.

21 McKinley, 86.

22 McKinley, 85.

23 Remember, this phrase was applied to Calvin by his former colleagues.

24 McKinley, 19-20.

25 Did Calvin and reconcile Dentière? Scholars differ. McKinley believes it possible, on account of attributing to Dentière a 1561 preface to Calvin’s sermon on 1 Timothy 2:12 titled on How Women Should Be Modest in Their Dress. Backus is doubtful about Dentière authoring the preface to Calvin’s sermon: “It is very difficult to believe that Calvin’s attitude to women speaking out on religious issues altered between 1546 and 1561” (Backus, “Women around Calvin,” 109). See McKinley, p. 87 and 93, re the similarities between the Very Useful Epistle and the preface to Calvin’s sermon. Both list the author as “M.D.” (ie, Marie Dentière), and both end with a reference to froment (wheat), the last name of her husband Antoine. “The imprint of Froment at the end of both works implies [Froment’s] involvement in those projects. Both works are framed by the wife’s initials or name at the beginning and the husband’s name at the end, suggesting that the couple collaborated on their production” (p. 87).

26 Bruening, 309.

27 McKinley, 53-54.