Neither Blender Nor Computer

Photos by Jason Leung (left) and Andrea Niosi (right)

1How important are metaphors? Metaphors are like lenses: they change our vision, focusing so that certain aspects of reality are seen more clearly.

Many of our words arise from metaphors, but through countless repetition we lose sight of the metaphor until we assume the word has explicit, literal meaning. For example, consider the word “comprehend”: we use to it indicate cognitive understanding, but the literal Latin meaning is “to grasp, seize, comprise.” We also use what we consider the (actual) metaphor “grasp” to indicate comprehension. Eg, “The student has a sufficient grasp of the material.”2

“Processing” is one of those words. As a therapist, it is one of the most ubiquitous words I hear, and even say myself. But I feel unsettled whenever I use the word. “I just need time to process this.” “Thank you for listening and helping me process.” “You need safe space to process your trauma.” What does that even mean?

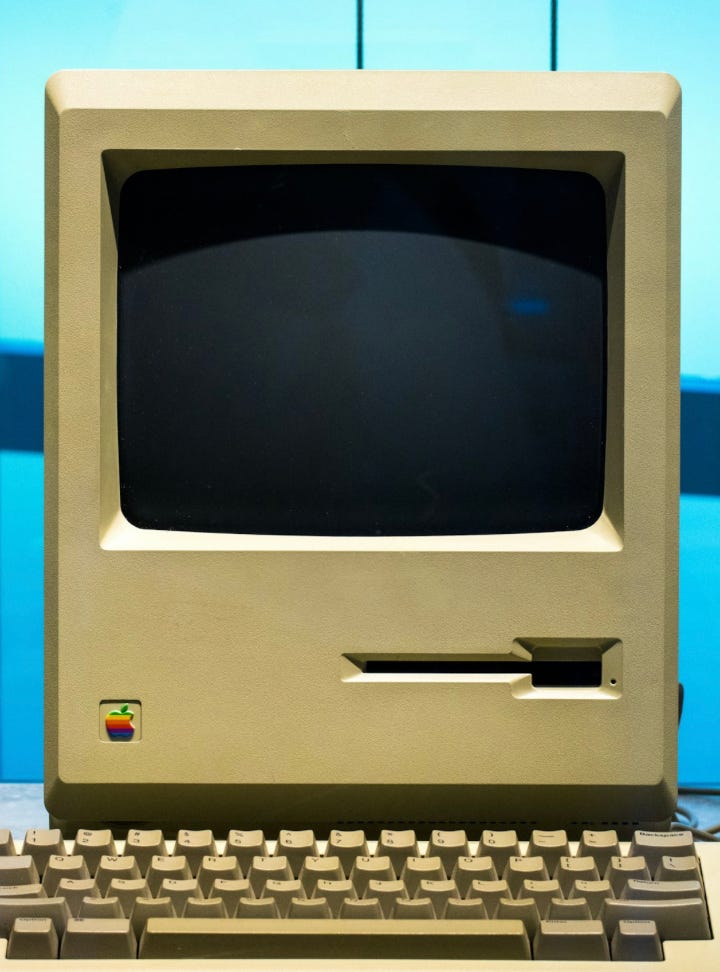

Two possibilities occur to me, both from the mechanical world: we process food in a “processing” machine; and computers “process” information. Both senses are given by the Oxford English Dictionary:

-

To purée or liquidize (food) in a blender, food processor, etc.;

-

To register or interpret (information, data, etc.).

The word itself comes from the Latin roots meaning simply to “go forward”, and that meaning ties to, say, how we distinguish between content (what is done or said) and process (how it is done or said), which is another meaning: “to deal with (something), esp. according to an established procedure.”

But when we talk about “processing” something—whether an idea or an experience—it denotes more than movement or manner; it’s about bringing things together, integrating, incorporating, absorbing. Given the common metaphors of food processing and information processing, I wonder if “process” is the best word for the mental/emotional sense we often mean.3

Ian McGilchrist suggests there is limitation with the computer information processing metaphor:

“[N]ew experience of any kind...engages the right hemisphere. As soon as it starts to become familiar or routine, the right hemisphere is less engaged and eventually the ‘information’ becomes the concern of the left hemisphere only…Understandably this has tended to be viewed as a specialization in information processing, whereby ‘novel stimuli’ are preferentially ‘processed’ by the right hemisphere and routine or familiar ones by the left hemisphere. But this already, like any model, presupposes the nature of what one is looking at (a machine for information processing). What would we find if we were to use a different model? Would perhaps something else emerge?”4

We need a different model. The underlying metaphor of therapeutic processing should neither be a food blender (I shudder to consider the implications), nor a computer.

Neither blender nor computer. Maybe stomach?

I believe we already have a different model and a better metaphor. It comes from Deuteronomy and Moses’ divine instruction to the people of Israel as they prepare to follow God’s mission into the land of promise. In Deuteronomy 8:3 Moses gives Israel this well-known instruction:

“Man does not live by bread alone, but man lives by every word that comes from the mouth of the LORD.”

We feed and sustain ourselves on bread, or food, but that is not all. God also created us to find nourishment from his words. Jesus knew this, which is why he quoted Deuteronomy 8:3 when Satan tempted him to turn a stone into bread. It’s also why the other Scriptures Jesus quotes to rebuff Satan come from nearby in Deuteronomy (Deut. 6:13 in Matt. 4:10, and Deut. 6:16 in Matt. 4:7). Jesus wasn’t just making mental reference to an abstract truth that God’s word sustains. He was living out that reality. He had already nourished himself on the live-giving truth that God’s words give life, as well as the life-giving truths that God alone is to be feared and served, and that testing God is forbidden.

What is the best metaphor to describe receiving nourishment from words? Philosopher Robert Roberts describes human beings as “verbivores”, creatures that eat words. Roberts combines “verbivore” from the Latin “verbum”, meaning word, and “voro”, to devour or swallow. This describes how words, like food, enters our bodies: through the act of eating and swallowing. The next stage would be digestion, so Roberts also describes humans as “word digesters”. He comments on Dueteromony 8:3, “Whoever feeds on the word of God lives; whoever does not take this word into himself, ruminate upon it, swallow it, and digest it into his very psyche, starves himself as truly as he would if he quit eating physical food.”5

Digestion is also a preferred metaphor of psychotherapist Bonnie Badenoch. She uses it in this definition of trauma:

“any experience of fear and/or pain that doesn’t have the support it needs to be digested and integrated into the flow of our development.”6

Why is that connection important? Because trauma, or any life experience, is not “processed” the way a computer moves electronic information through circuits (and certainly not the way a blender dices and mixes up food). The processing metaphor is disembodied, and keeps the focus on our minds. Digestion better fits a Biblical worldview that includes our souls and bodies, all that makes up the human self.

Science has discovered that our stomach has hundreds of millions of neurons, so that some refer to it as the “belly brain”, aka the enteric nervous system. Digesting and metabolizing life is a wholistic process. It uses not only the verbal precision of the left hemisphere, but also the subliminal gut-level wisdom of the right hemisphere. We refer to a “gut feeling” as a way of knowing something that cannot be expressed clearly with words. The ancients knew this intuitively and associated many emotions with physical organs; e.g., compassion in the New Testament literally means bowels. We can also see this connection in the metaphoric word sometimes used for “meditation” in the Hebrew bible, which is used in Isaiah 31:4, “like a lion…that gnaws and chews and worries its prey” (The Message).

In order to digest life, especially pain, suffering, loss and trauma, we need to gnaw and chew in order to break it down so that our experience can be metabolized.

Next time you find yourself expressing the need to “process” events or speech, try using “digest” instead. See how it feels. Perhaps, as McGilchrist observes, something else will emerge when you use this metaphor. Does it invite you into a deeper experience? Perhaps one that relies less on the explicitness of verbal precision, and more on the ruminative, meditative nature of reflection? What happens when you imagine digesting what God says about himself and about you. Can you imagine God’s Word quite literally taking up deeper residence in your body?

Quote from Bonnie Badenoch

“In Eastern cultures, there has been less of a tendency for our sense of self to move upward into our heads. For example, we in the West might say a persistently angry person is “hot-headed,” but if we were from the East, we might say something like “his belly rises easily.” As we dwell with this accumulating research and seek to feel its meaning in our bodies, we may find that our awareness expands downward to listen with equal respect to the voices of these two brains [head and stomach] as they carry on their continual conversation.”7

Question

How are you digesting these reflections?

1 This subtitle comes from Mark Johnson’s book The Body in the Mind: The Bodily Basis of Meaning, Imagination, and Reason. I found it at a local thrift store, but the title will have to do for now, as a cursory glance showed it is way beyond my reading ability.

2 Once you start looking for these it can be quite distracting! In that paragraph I overlooked the metaphors behind “understand” (stand underneath) and consider, which might originate from Latin com “with, together” and sidus “heavenly body, star, constellation”. And of course, metaphor itself comes from the Greek roots meta “after, behind” and phero “bear, carry”.

3 Indeed, OED lists 1973 as the first use with the sense “To come to understand or accept (something, often a complex emotion or difficult personal situation).” That is the same time period that cognitive therapy was being developed, and when computers provided a natural analogy for addressing cognitive errors in logic.

4 Iain McGilchrist, The Master and His Emissary: The Divided Brain and the Making of the Western World (Yale University Press, 2018), p. 94.

5 Robert C. Roberts, “Paramters of a Christian Psychology”, in Limning the Psyche: Explorations in Christian Psychology, edited by Mark R. Talbot and Robert C. Roberts (Grand Rapids: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 1997), p. 81.

6 Bonnie Badenoch, The Heart of Trauma: Healing the Embodied Brain in the Context of Relationships (W. W. Norton & Co., 2018), p. 23.

7 Badenoch, The Heart of Trauma, p. 95.