Prayer & Meditation VII - The Power of Attention

Advocates of mindfulness, as rooted in Buddhist tradition, argue for the power of awareness that comes from attention to the experience of awareness itself. Whatever neurological benefits may accrue, and I’m willing to acknowledge such, the practice is antithetical to Christian meditation. In the words of Stephen Charnock, attempting to achieve awareness of awareness “is to delight in the act or manner of thinking, not in the object thought-of: and thus these thoughts have a folly and vanity in them.” Although at times appropriately directed inward in self-examination, the ultimate aim in meditation is heavenward to, as Gregory of Sinai put it, “mindfulness of God.”

That being said, there is power in attention worth reflecting on. According to one influential leader of the early desert monastic movement, Evagrios of Pontus,

“If you seek prayer attentively you will find it; for nothing is more essential to prayer than attentiveness. So do all you can to acquire it.”

Thomas Manton preached a sermon dealing with spiritual attention titled “How May We Cure Distractions In Holy Duties?” Surely everyone can relate to this observation, that distractions

“chiefly...haunt us in prayer; and, of all kinds of prayer, in mental prayer, when our addresses to God are managed by thoughts alone, there we are more easily disturbed.”

This is a symptom of being not merely finite but fallen human creatures. Our distractions are evidence of mental and spiritual weakness. We feel powerless over distraction, but distraction can also be culpable. Manton wrote,

“You lose your advantage for want of attention. Allowed distractions turn your prayers into sin, and make them no prayers. When the soul departeth from the body, it is no longer a man, but a carcass: so when the thoughts are gone from prayer, it is no longer a prayer; the essence of the duty is wanting.”

Perhaps this is so common sense that we don’t even pay much attention to the role of attention. Especially if you’re a parent or a teacher, you know the vanity of talking when others aren’t listening. But consider Manton’s statement: “you lose your advantage for want of attention.” Why is that?

Curt Thompson discusses the importance of attention in his book Anatomy of the Soul. He agrees with Manton’s observation of our difficulty with distraction:

“But despite the fact that we believe that paying attention is important, the truth is we live much of our lives inattentively.”

He then states that “Attention can be considered the ignition key of the mind.” What a curious yet instructive metaphor. Thompson’s work is heavily influenced by Dan Siegel, who stated that

“Attention itself can be defined as a process that directs the flow of energy and information.”

That is to say, attention is like “the beam of a flashlight along a dark pathway”, illuminating your steps and directing what your mind notices and takes into awareness. This flashlight of attention is also the ignition key because it brings the mind online to process what is observed and taken in, whether through bodily signals (interoception), external phenomena through the 5 senses (perception), or in the spiritual realm with what Calvin termed the “sensus divinitatis”, sense of the divine.

One of the fundamental principles of soul healing is that “having awareness gives us a choice to make a change.” Attention is the effort of the mind to strengthen and increase awareness. And as Siegel often states,

“where attention goes, neural firing flows, and neural connection grows.”

If there is healing power in our natural ability to attend to mind, brain and relationships – what Siegel refers to as “triception” – how much more potential is there when we focus our attention on “the things that are above, where Christ is, seated at the right hand of God” (Colossians 3:1)?

Indeed, it is no coincidence that when the apostle Paul deals with the Christian duty of mortification, putting sin to death, in the near context he calls Christians to set their minds on spiritual things. After calling the Colossian believers to “set your minds on things that are above” in 3:1-4, he writes, “Put to death therefore what is earthly in you” (3:5). In Romans 8:13 Paul exhorts believers that “If you live according to the flesh you will die, but if by the Spirit you put to death the deeds of the body, you will live.” The previous context of Romans 8 details the conflictual contrast between the flesh and the S/spirit, and verses 5-6 explain,

“For those who live according to the flesh set their minds on the things of the flesh, but those who live according to the Spirit set their minds on the things of the Spirit. For to set the mind on the flesh is death, but to set the mind on the Spirit is life and peace.”

So the potential for putting to our sin to death is conditioned upon the attention of our minds.

Now, we must not think of “mind” in a reductionistic fashion, limiting it to mere intellectual/cognitive activity. Manton links the attentional and affective aspects of the mind thus:

“You find this by daily experience; when your affections flag in an ordinance, your thoughts are soon scattered; weariness makes the way for wandering; our hearts are first gone, and then our minds. You complain you have not a settled mind; the fault is, you have not a settled love.”

Which comes first, a settled mind, or a settled love? Manton says we need a “settled love” in order to have a “settled mind”. On the other hand, mortifying sin through setting the mind on the things of the Spirit serves to increase our affections for God. The truth is that these are reciprocal. The Spirit renews our loves so that we love God, and that moves us to set our minds on the things of God. And the more we set our minds on the things of God, the more our loves and affections are renewed.

The heavy lifting on our part is, as Peter put it, to “gird up the loins of your mind” (ESV: “preparing your minds for action”, 1 Peter 1:13). When our minds are ready for action, we get to work. We act with our minds. We “think about these things” (Philippians 4:8). The biblical word for this is meditation. And like an athlete would “gird up the loins” for physical action in the gymnasium, which also requires consistency and repetition, so must we with meditation.

Theophan the Recluse made this observation in a letter to someone asking for counsel on prayer which applies equally to meditation:

“You write that you are having trouble controlling your thoughts; they scatter easily, and praying does not proceed as you wish; and that, in the midst of the day, in the midst of toil and association with others, there is little remembrance of God. Instantaneous prayer life is impossible. You must make a strong effort to control your thoughts, at least to some degree. Prayer life does not come about as you expect – by just wishing for it, and suddenly, there it is. This does not happen.”

We all know that when it comes to getting in shape or losing weight, it doesn’t happen “by just wishing for it.” It takes work! The same goes for our spiritual life and setting our minds on the things of God. Theophan wisely wrote,

“Prayer of the heart comes when one makes an effort; to those who do not strive, it will not come.”

By focusing our minds on Scripture in set times of meditation, we engage the ignition key of attention and open ourselves to the work of the Spirit who brings “life and peace” (Romans 8:6).

John Owen’s treatise on this topic, The Grace and Duty of Being Spiritually Minded, takes its starting point with Romans 8:6. He too was aware that in order to benefit from setting our minds on Christ, there are no shortcuts and quick results. He counseled that

“General thoughts and notions of heaven and glory do but fluctuate up and down in the mind, and very little influence it unto other duties; but assiduous contemplation will give the mind such distinct apprehensions of heavenly things as shall duly affect it with the glory of them.”

That word “assiduous” might sound odd; it comes from Latin assiduus, meaning “attending; continually present, incessant; busy; constant,” and from the verb assidere, “to sit down to, sit by” (thus “be constantly occupied” at one’s work).” So we might paraphrase Owen as advocating for “constantly attentive contemplation”.

Yes, that sounds like work. But the results are worth it. Peter Toon, an Anglican theologian, wrote multiple books on Christian meditation, and his reflection on the effects of meditation is a fitting close to this post:

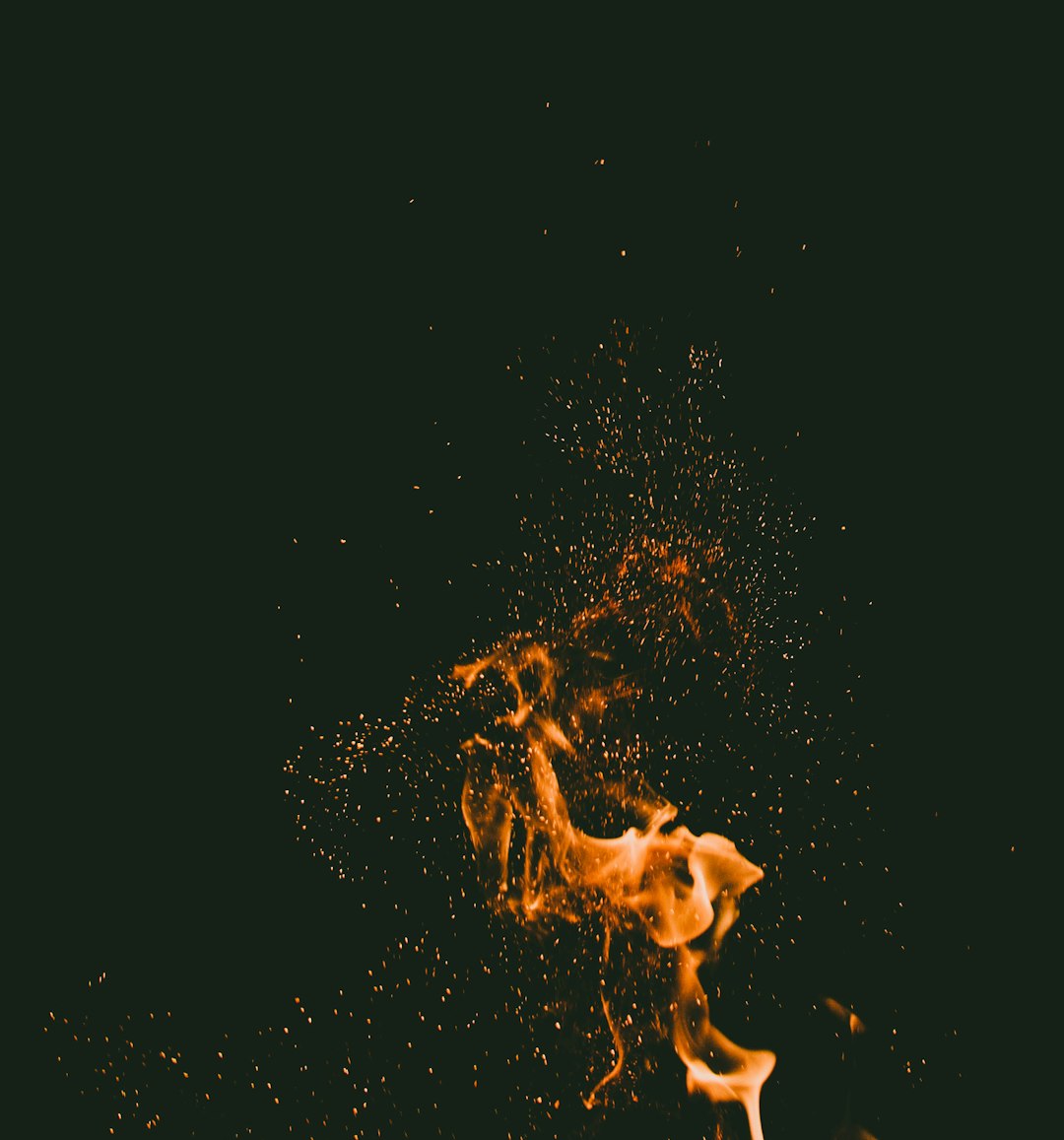

“The meditator cannot expect to be a totally changed person, losing all hesitancy, inhibition, and lack of motive to love the neighbor, within a day or two. The strengthening of the will, in its resolve and commitment to doing God’s will practically in real-life situations, is a gradual process. However, like putting dry wood on fire, the action of the will does increase the love of God in the heart and makes the next action of love that much easier. In fact, we can see the whole process through the imagery of a fire. It is kindled originally by the work of the mind (understanding, memory, and imagination), it leaps up in flames as desires for God and his glory and love of him and his name are created, and it is then kept burning both by acts of love and by further meditation.”