Reading for Transformation

A few years ago I realized the need to grow as a spiritual reader. If I could see a graph correlating my rate of reading and my rate of sanctification, I probably wouldn’t like the results. So I began thinking about how I approach reading and what I might change. What started with a hand-written list of practical tools and suggestions led to a deeper exploration of what is involved in the act of reading. Not just cognitively, but spiritually. Reading is transformative when it is contemplative. And that requires prayer.

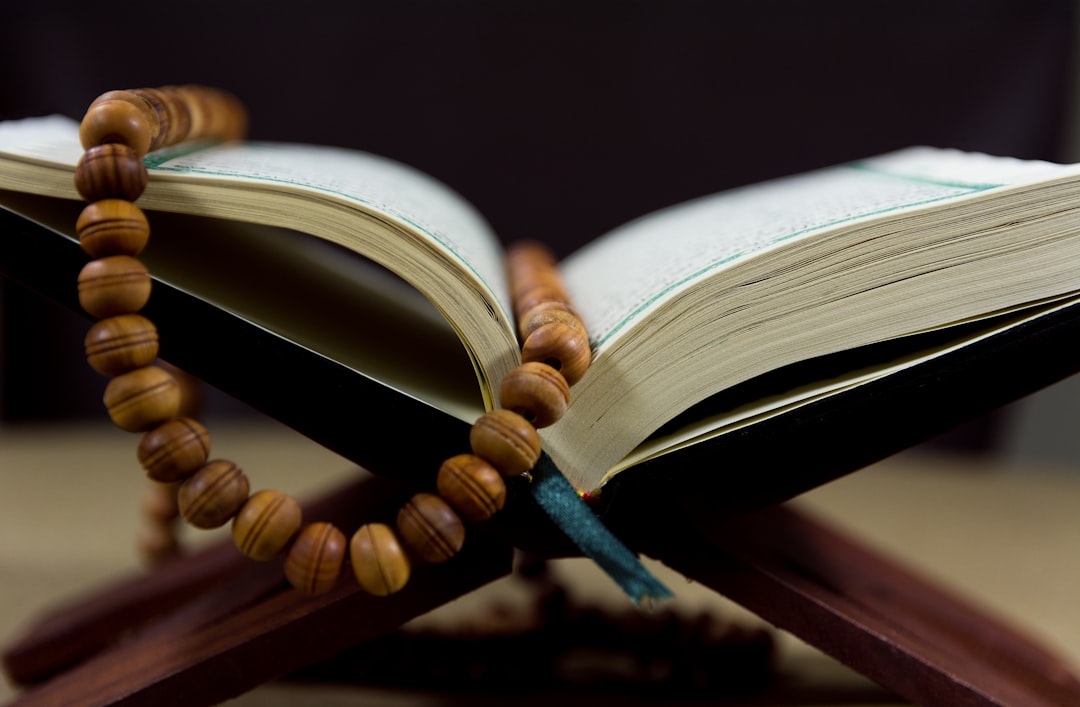

Photo by GR Stocks on Unsplash

Reading has the potential to form us in many respects, one of which is through coming to know and understand what was previously unknown. There is no better way to do this then to read original texts on their own terms, striving with the text and dialoging with the author until comprehension is reached.

“Our mind has the task not of repeating but of comprehending - that is, we must “take with” us, cum-prehendere, we must vitally assimilate, what we read, and we must finally think for ourselves.”1

If we think for ourselves, we don’t think by ourselves. Contemplative reading follows Paul’s exhortation to Timothy to “Think over what I say, for the Lord will give you understanding in everything” (2 Tim. 2:7). We read, and think as we read, but not with self-reliant effort. This contrasts Mortimer Adler’s advocacy of active reading as

“the process whereby a mind, with nothing to operate on but the symbols of the readable matter, and with no help from outside, elevates itself by the power of its own operations.”2

Adler’s approach obviously doesn’t fit the manner in which we should read God’s Word. And while other books may not have the promise of divine illumination, that doesn’t mean we should read them as autonomous creatures. In reading any kind of book, we recognize that God “sets created intellect in motion, arousing the exercise of the powers which God bestows and of whose movement he is the first principle.”3

So, we read in the second person, not the third, praying to God for illumination, insight, understanding, inspiration, and transformation. Such prayers attend to the aims of reading. Prayer must also address the attitudes of mind and heart required by contemplative reading. This is expressed by Psalm 119:34:

“Give me understanding, that I may keep your law and observe it with my whole heart.”

The psalmist does not pray for understanding for its own sake, nor is understanding merely intellectual, as in modern thought. Understanding is attitudinal and behavioral; it is humble, submissive, and obedient. Seeing “understanding” in this way explains why prayer must be the beginning, middle and end of reading, as John Owen advises:

“all of these activities, and any others of similar nature, are always to be preceded, accompanied, and closed by continuous and heart-felt prayer.” 4

I will share many concrete techniques in this series, but I don’t think I can improve on that advice: make prayer the beginning, middle and end of your reading.

Quote from Theophan the Recluse5

During such occupations [as reading], you should continually keep in mind the main goal – impressing the truth on yourself and awakening the spirit. If reading or discourse does not bring this about, then they are but idle itchings of the tongue and ears, or empty discussion. If it is done with intelligence, then the truths impress themselves and rouse the spirit, and one thing aids the other. But if the reading or discourse digresses from the proper image, then there is neither one nor the other’s truth – is stuffed into the head like sand, and the spirit becomes cold and hard, smokes over and puffs up. Impressing the spirit is not the same as searching for it. This requires only that you clarify what the truth is, and hold it in your mind until they bond together. Let there be no deductions or limitations – only the face of truth.

Recommended Reading

I am no expert, and there are many good books, both old and new, that explain the ideal practices of reading. I will mention some of these along the way, and I would love to hear your practices and recommendations as well!

Eat This Book, by Eugene Peterson. Although Peterson focuses on spiritual reading of Scripture, there is much to be gleaned for reading in general. I also recommend this book because Peterson led me to my next recommendation for this week:

In the Vineyard of the Text: A Commentary to Hugh's Didascalicon, by Ivan Illich. This is one of the most fascinating and inspiring books about reading I have ever read. Here is Peteron’s blurb about it: “Hugh of St. Victor, one of our seminal figures in the field of spiritual theology, in about A.D. 1150 wrote the first book on the art of spiritual reading (the Didascalion), treating it as an intricate and comprehensive ascetic discipline. Ivan Illich's commentary on the book provides us access to this incomparable trove of insights, counsel, and urgency embedded in the practice of spiritual reading.

Question

What biblical prayers come to mind that could be used as prayers for reading? For example, how about praying Psalm 119:34 before, while and after you read? “Give me understanding, that I may keep your law and observe it with my whole heart.”

1 A. G. Sertillanges, The Intellectual Life: Its Spirit, Conditions, Methods (Washington D.C.: The Catholic University of America Press, 1987), p. 170.

2 How to Read a Book (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1940), p. 8.

3 John Webster, The Domain of the Word (New York: Bloomsbury T&T Clark, 2012), p. 57.

4 John Owen, Biblical Theology (Orlando, FL: Soli Deo Gloria Publications, 1994), p. 701.

5 "The Path to Salvation," (Platina, California: St. Herman of Alaska Brotherhood, 1998), pp. 243-244.