Records of the Liberating Gospel

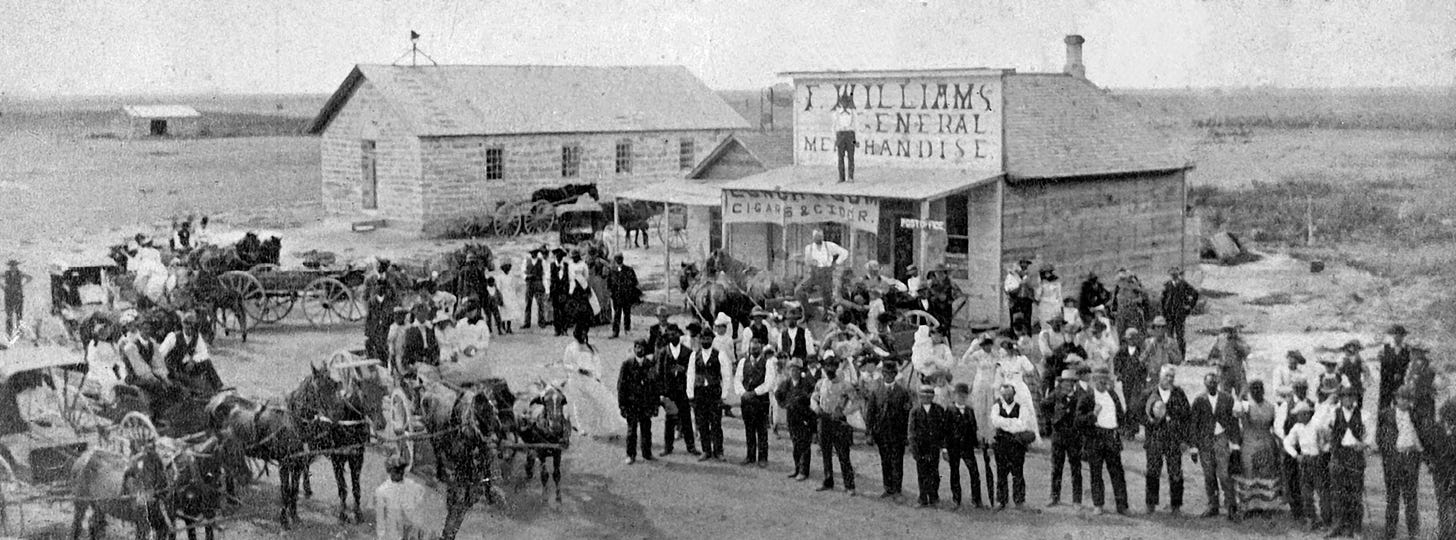

Nicodemus Town Square in 1885, image courtesy of the National Park Service

In the last Thesis 96 post, Records of the Dangerous Gospel, I showed some history of how the Gospel of John has been misused to justify violence and oppression. My interest in this question is not merely how people have read John, but how people have lived from their readings of the Fourth Gospel. If oppressive anti-Semitism is a misreading of John, what happens when people read John rightly? How do they live when the Light of the world shines gloriously through the words, images and stories of the Johannine Jesus? Here is just one example from 148 years ago, as studied by Rosamond C. Rodman: “Nicodemus, one of the first all-black settlements in Kansas, and the sole remaining town founded by and for African Americans at the end of Reconstruction.”1

The idea for Nicodemus, Kansas, founded in 1877, came from two African American ministers, William Smith and Thomas Harris. Along with a small group of investors, they formed the Nicodemus Town Company and sold plots to prospective residents for $5.

Image courtesy of Nicodemus Historical Society

As the title of Rodman’s article indicates, the really curious thing about Nicodemus is, why choose that name? Shortly after the Emancipation Proclamation, a white abolitionist named Henry Clay Work wrote a song titled ‘Wake Nicodemus’ which became relatively well-known and told of a fictional slave named Nicodemus. He died before the Emancipation, and the song records his dying wish: “‘Wake me up!’ was his charge, ‘at the first break of day / Wake me up for the great Jubilee!’2

The Nicodemus Town Company used this song to advertise their all black settlement, but invested it with subversive meaning with slight changes to the lyrics. Rather than name their town after a made-up legendary slave, they named it after the Nicodemus of the Gospel of John. Rodman connects this naming to the immense value Scripture had for African Americans. “Bible reading became a popular locus for resistance to white oppression, although learning to read was quite dangerous.” So dangerous, and yet so desirous, that they would “slip out at night and meet in a deep gully whar dey would study by de light of light’ood torchers.”3

It is understandable, then, that these recently liberated men and women resonated with the story of Nicodemus:

“Nicodemus came to Jesus in the same way African Americans came to the Bible: at night and in secret, understandably afraid of the consequences.”

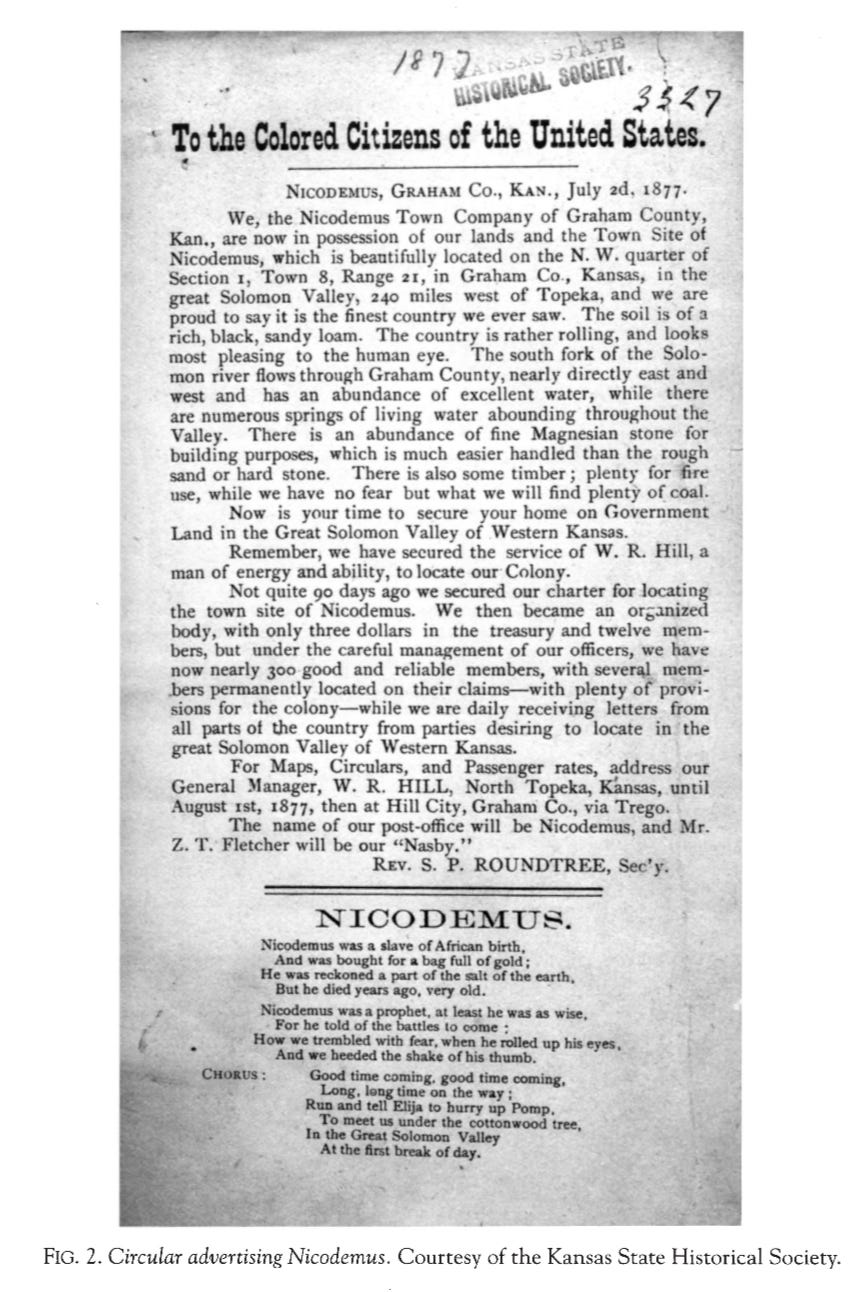

The view that naming their settlement Nicodemus was more inspired by the Gospel of John than Henry Clay Work’s song is also evidenced by Rev. Roundtree’s advertisement. He describes the topography of Graham County, KS, “in the great Solomon Valley”, which takes its name from the Solomon river. The description of the river and surrounding water sources is striking: “The south fork of the Solomon river flows through Graham County, nearly directly east and west and has an abundance of excellent water, while there are numerous springs of living water abounding throughout the Valley.”4

From Rodman, p. 54.

Anyone familiar with John’s Gospel can recognize these allusions5:

-

John 4:14 “But whosever drinketh of the water that I shall give him shall never thirst; but the water that I shall give him shall be in him a well of water springing up into everlasting life.”

-

John 7:38 “He that believeth on me, as the Scripture hath said, out of his belly shall flow rivers of living water.”

-

John 10:10 “I am come that they might have life, and that they might have it more abundantly.”

Roundtree’s description of that area’s water is notably different than that from Robert McBratney, who kept a detailed diary in late 1869 while exploring the Solomon Valley for potential railroad expansion. His October 21, 1869 entry described the Solomon River as “Water clear and pure, &excellent for drinking.” On October 24 he wrote, “The water of the Solomon and its tributary is clear, pure and hard, and known as limestone.”6

Roundtree could have chosen simple adjectives like “clear” and “pure,” but he did not. The repetition of “abundance/abounding” coupled with the phrase “numerous springs of living water” seems like a clear allusion to John’s Gospel, especially given the town name Nicodemus. These allusions likely functioned as a “hidden transcript” signaling deeper spiritual meaning:

“Roundtree disguised the biblical Nicodemus within the majority cultural expression (the “public transcript”) that the popular song afforded. By virtue of the multivalence inherent in the name Nicodemus, he insinuated meaning to his audience (recently freed slaves), a meaning that was disguised to the audience of the dominant culture.”7

Some scholars believe that the Gospel of John is itself a hidden transcript, a text that helped an oppressed, minority group (Christians, mostly Jewish and some Gentile) successfully navigate the dominant cultures they encountered in Rome and Judaism. After studying John in depth for almost 2 years now, focusing on the original context and the perspective of spiritual abuse, it makes all kinds of sense that the African Americans who settled in Nicodemus found special inspiration in John’s Gospel.

“Naming this place Nicodemus is a poignant example of how African Americans arrogated to themselves the Bible that had been used, in the hands of slaveholding whites, to justify their enslavement and domination. It signifies their endurance and ultimate victory over those forces, and reveals their intellectual and creative appropriation of [the Bible]…Naming a place Nicodemus reveals the arts of resistance and disguise enacted by peoples to retain their own distinctive history, to make the Bible suit them and their own imaginations.”8

That last line off the mark. These African Americans didn’t “make the Bible suit their imaginations.” They read with the grain of the Bible. They saw that the Gospel of John was written for an oppressed people, living in fear of the dominant group who used the Word of God to justify violence against those who challenged the status quo (eg Jn 9:34, 12:10-11, 16:2). With the name Nicodemus, they signaled what John indicates was possible for those living in fear: being born again into the kingdom of God with new identities, not as slaves, not as those “spiritually” free yet physically enslaved, but “free indeed” (John 8:38). Indeed, the Johannine Jesus explicitly declared, “I no longer say you are ‘slaves’…I have called you ‘friends’” (15:15).

Quote from David Rensberger

“‘Anyone who makes himself a king is defying Caesar’ (John 19:12). By refusing to grant allegiance to Caeser or to acknowledge his authority, Johannine Christianity provides the fundamental prerequisite for undermining his rule. By giving allegiance instead to Jesus as King, it lays the groundwork for an ongoing nonviolent resistance to every nationalism, every oppression, and every ideology that would play the role of Caesar. In this way John makes justice possible, by removing from injustice the aura of sovereignty with which it surrounds itself and by pointing the way toward freedom in the truth of the sovereignty of God.”9

Question

What do you make of these stories of John being used for both anti-Semitism and African American liberation? How are you wrestling with that tension?

Subscribe

1 Rosamond C. Rodman, “Naming a Place Nicodemus,” Great Plains Quarterly 28, no. 1 (Winter 2008): 48.

2 Rodman, 52.

3 Rodman, 56.

4 Rodman, 54.

5 As a guess toward an English translation in use at the time, I took these quotes from The New Testament of Our Lord and Saviour Jesus Christ, published by the Tennessee Bible Society in 1861. It claims to be an original translation, but these verses are word for word the same as the KJV.

6 Martha B. Caldwell, ed., “Exploring the Solomon River Valley in 1869,” The Kansas Historical Quarterly 6, no. 1: 60-76.

7 Rodman, 55.

8 Rodman, 58.

9 David Rensberger, Johannine Faith and Liberating Community (Philadelphia: The Westminster Press, 1988), 118.