When Empire Comes to Church, Part 3

Lluis Borrassa (1411-13), Terrasa (Catalonia), Church of Sant Pere

This is the third post in a series on empire in the Gospel of John and Peter’s use of violence in John 18:10. If you haven’t read those yet, see part one and part two.

How can a follower of Jesus follow a leader of Jesus-followers if that leader did not repent of his denial of citizenship within the peaceful empire of Jesus? (Cf John 18:36)

Peter’s triple denial of following Jesus was public and well-known. Peter’s triple declaration of love for Jesus was public and well-known.

Peter’s imperial violence was likewise well known, and his repentance of abusing his spiritual power needed to likewise be public and well known.

We might say, the first is more emphatic than the latter. Three is more than one, after all: three I-am-nots call for three I-love-yous. But that one slice of the the sword cut deep into Malchus, and Peter needed to plunge deep into repentance.

That, I believe is the meaning of John 21:7:

The disciple, the one Jesus loved, said to Peter, "It is the Lord!" When Simon Peter heard that it was the Lord, he tied his outer clothing around him (for he had taken it off) and plunged into the sea.

This is baptism in symbolic form. So, a symbol of a symbol, if you will. I will try and briefly explain this way of understanding Peter’s plunge and then draw some inferences for our day. Simply put, the spirit of empire must be washed away.

Waters of Empire

First, the narrative context. Significantly, only John names the Sea of Galilee as the Sea of Tiberias, ie Tiberius Julius Caesar Augustus, Roman emperor from 14-37 CE. This was sea underneath the imperial control of Rome. Very few commentaries explore this. Actually, I have only found one commentary that does, but only in passing.1 Warren Carter, in John and Empire: Initial Explorations, observes that John referring to the Sea of Galilee as the Sea of Tiberias “evokes the emperor Tiberius as a reminder that Rome’s claims to sovereignty, even over bodies of water, are limited by God’s life-giving power.”2 Arthur M. Wright Jr. devotes a recent article to that very point, and he gives some helpful background context:

Herod Antipas founded the city of Tiberias around 20 CE on the western side of the lake in honor of his patron, Emperor Tiberius. Located on the west coast of the Sea of Galilee, the city became the capital of the Galilean region, providing oversight and control of the Galilean fishing industry as well as general commerce in the region. A key component of the imperial strategy was to funnel taxes from the region to Rome. By evoking the name Tiberius (6:1 and again in 6:23 and 21:1), the author recalls the Roman occupation and dominance of the region…Describing the lake in relation to the city of Tiberias [in 21:1], the text recognizes that the disciples are within Herod Antipas’s sphere of imperial control for the Galilean region and, more specifically, the Galilean fishing industry. The disciples cast off onto the lake to go fishing under the shadow of imperial Rome.3

Wright is primarily interested with the miraculous catches of fish in both John 6 and John 21. Fascinating stuff, as hardly any commentator takes the time to wonder why John mentions Tiberias. Just like it is significant that the disciples are fishing in imperial waters, I believe it is significant that Peter plunges, baptism-esque, into imperial waters.

Tossing Swords, Tossing Selves

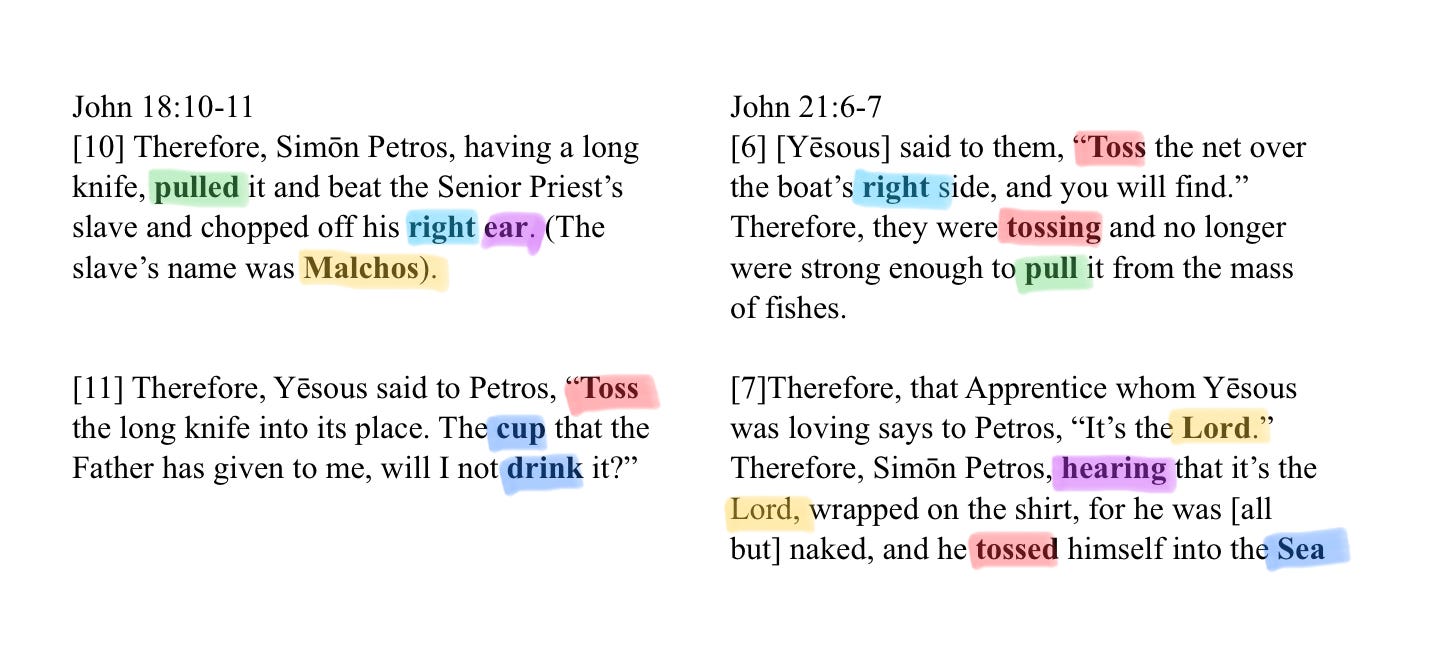

Which takes me to my second point. John, ever the careful writer, created symbolic parallels between Peter’s plunge into the sea and his sword’s plunge into Malchus. But that word-play on plunge is mine, not John’s. It is helpful to see John’s parallels side-by-side (translation from

Scot McKnight ’s The Second Testament)4:

As Peter pulled his sword and cut off the right ear of Malchus, the disciples tried to pull the net of fish from the right side of the boat. As Jesus told Peter to toss his knife into its place, so Peter tossed himself into the sea. If we look for parallels at the conceptual level, we can also see how the cup which Jesus was to drink on the cross corresponds to the Tiberian sea—both symbols of empire, and, as we’ll see next, judgment.

Tossed Into The Sea

Third and finally, that phrase “tossed/threw into the sea” is distinct Johannine language. Seven times in Revelation “thrown into the sea/lake” is language of judgment. Rev 18:21 is a fitting example:

Then a strong angel took up a stone like a great millstone and threw it into the sea, saying, “So will Babylon, the great city, be thrown down with violence, and will not be found any longer.”

This is fitting, because baptism is a symbol of judgment. We often forget this, but passing through water is usually both salvation and judgment. At the beginning of the Fourth Gospel, the water baptism which John the Baptizer administered was an invitation to repentance (1:23-28). In John 15:6 Jesus says branches that don’t remain in him will be “thrown/tossed into the fire”, reminiscent of “tossed into the sea”.

Peter did not toss himself into any generic waters. He plunged deep into the sea under the dominion of emperor Tiberius. Likewise, it is not any old city that will be thrown into the sea like a millstone; it is Babylon, that is, Rome, and all empires like it.

Sea of Tiberias, ie Rome, ie, Babylon, ie, the Sea of Babylon.

As Peter “tossed” his sword away, Peter “tossed” his violent self into the sea of empire, washing away his violence in imperial waters, rising from them to be a safe shepherd who feeds and tends Jesus’ flock.

Radical Repentance

In John 13:10 Jesus says, “One who has bathed…doesn’t need to wash anything except his feet, but he is completely clean.” I wonder if there is some Johannine irony between John 13 and John 21. Isn’t it ironic that Peter protested, “Lord, not only my feet, but also my hands and my head” (13:9), and then washed his entire body from head to toe in the Tiberian Sea? Maybe Peter was more right than he knew. It just wasn’t yet time for him to be bathed head, shoulders, knees and toes. The need for that kind of repentance only becomes manifest after egregious sin and abusive power that profoundly contradicts the servant king. Peter demonstrates such deep repentance for shepherds.

Many will not take the plunge, as

Chuck DeGroat recently testified. Like Peter pulling on his clothes before meeting Jesus, many will not allow their shame to be seen5.

But I believe this story of Peter traced between 18:10 and 21:7 is there for a reason. We see Peter succumb to the spirit of empire and rationalize abuse of spiritual power. Then we see Peter washed clean of empire. Significant on its own, that sequence, along with the threefold restoration in 21:15-17, is really preparation for the radical repentance we see in Peter’s Christ-like death:

“Truly I tell you, when you were younger, you would tie your belt and walk wherever you wanted. But when you grow old, you will stretch out your hands and someone else will tie you and carry you where you don’t want to go.” (21:18)

This verse helped me understand a strange intertextual connection between John 21 and 2 Samuel 24. I became curious about these two passages when I saw that the noun form of the word for “breakfast” in 21:12, ariston, only occurs one time in the Greek Septuagint, in 2 Samuel 24:15. Here is the NETS Septuagint translation, with ariston in bold:

And there were days of wheat harvest, and the Lord gave death in Israel from morning till lunchtime, and the destruction began among the people, and seventy thousand of the men died out of the people, from Dan and as far as Bersabee.

Doesn’t look very significant at first glance, I know. But consider the context: God was angry against King David for taking a census of the people (2 Sam 24:1, 10). Through the prophet Gad, God gave David options for punishment in threes: three years of famine, three months of fleeing from enemies, or three days of death. Sounds familiar, right? Three denials, three “do you love me?”s, three “yes I love you”s. But there’s more. After the possible allusion with ariston, there is the phrase “stretch out [your/his] hand”:

And the angel of God stretched out his hand toward Ierousalem to destroy it, and the Lord was consoled over the evil and said to the angel who was destroying among the people, “It is much now; relax your hand.”

That is the same verb in John 21:18, ekteinō, where Peter will “stretch out his hands”.

“Ok,” you might be thinking, “still, where’s the connection?” The connection is not clear in our English translations of 2 Samuel 24:17, the verse following the two potential allusions in ariston (24:15) and ekteinō (24:16). Here is the CSB translation:

When David saw the angel striking the people, he said to the LORD, “Look, I am the one who has sinned; I am the one who has done wrong. But these sheep, what have they done? Please, let your hand be against me and my father’s family.”

But the Septuagint has a significant addition (which some English translations footnote). Here is the NETS translation:

And Dauid spoke to the Lord when he saw the angel hitting among the people and said, “Behold, I am—I did wrong, and I am the shepherd—I did evil, and these are the sheep; what did they do? Now let your hand be against me and against the house of my father.”

Wow. “I did wrong. I am the shepherd. I did evil.” What an admission. And the shepherd language brings us back to John 21. Jesus restored a shepherd—the threefold “fend/tend my sheep”—who was truly repentant. Who needed to be rewashed in radical cleansing. And with these allusions I think we can put David’s confession in Peter’s mouth, a model for all shepherds who have acted more like imperial rulers than protecting shepherds. Here is how this confession might go, with slightly modified language:

“Behold, I am—I did wrong, and I am the shepherd—I did evil, and these are the sheep; what did they do? Now let whatever my brothers and sisters—who listen for the Spirit on my behalf—deem necessary for my repentance be done to me.”

If more and more pastors, elders and leaders followed the paths of David and Peter, we might see empire being washed more and more away from the church.

Quote from Tom Thatcher6

“Jesus’ [footwashing] anticipates and precludes the emergence of anything like a new imperial order within his eschatological community. No one steps in to take the throne once the ruler of this world is cast out. In fact, there are no thrones, only footstools, and masters find themselves in the place of slaves, washing the filthy feet of the people over whom they have authority.”

Question

What do you think, does Peter’s narrative arc in John’s Gospel give you hope for pastors and Christian leaders who abuse their power? What are you thinking after reading these three essays about when empire comes to church?

1 “The reference to Tiberias, precisely because it seems so puzzling, causes the reader, Nicodemus-like, to pause and think. And it can be seen to make sense. Since "Tiberias" was a variant of Tiberius," the name of an emperor (A.D. 14-37) and one of the most prestigious names of the Roman Empire, it serves as a way of evoking that empire, as a way of setting the scene in the context of the whole world.” Thomas Brodie, The Gospel according to John: a literary and theological commentary (Oxford University Press, 2007), p. 260

2 Warren Carter, John and Empire: Initial Explorations (New York: T&T Clark, 2008), p. 168.

3 Arthur M. Wright, (2022). The emperor’s new loaves: Scarcity and abundance in John 6:1–15 and 21:1–14. Review & Expositor, 119(3-4), p. 411, 413.

4 I highlighted some additional potential parallels that might be more of a stretch: Malchos means king, a synonym for Jesus as Lord, kyrios; Peter cuts off Malcho’s ear, and he hears that “it’s the kyrios [Lord]”.

5 Although the symbolism of Peter’s action there in 21:7b is only slightly less mystifying than the oddly numbered 153 fish in 21:11.

6 Tom Thatcher, Greater than Caesar: Christology and Empire in the Fourth Gospel (Fortress Press, 2009) p. 138.