Church Liturgy and Systemic Corruption

What do you do when tradition has been tainted with trauma? What options do we have when religious custom has become corrupt? Do we cancel, like Calvin and the reformed tradition did with the Roman Catholic Mass? What if liturgies are not only theological errors but ethically harmful as well? If a religious tradition has become rooted in systemic injustice, what then?

Last week we considered the traumatic impact on Sabbath observance for the Johannine community after their expulsion from their Jewish society. Part of the Spirit’s treatment for that pain, through John’s Gospel, is to take what was tainted by trauma and give it new meaning. Corporate worship becomes connected to the healed religious scars of Jesus.

I believe something similar happens with the next feast mentioned in John 6: Passover. We will be better prepared to see this if we approach the story pastorally as well as theologically, as Mary Color rightly says: “For all we talk about John as a theologian, he’s a pastor. He’s caring for the genuine needs of his people.”1 More and more, I’m convinced we should refer to John as the Pastoral Gospel.

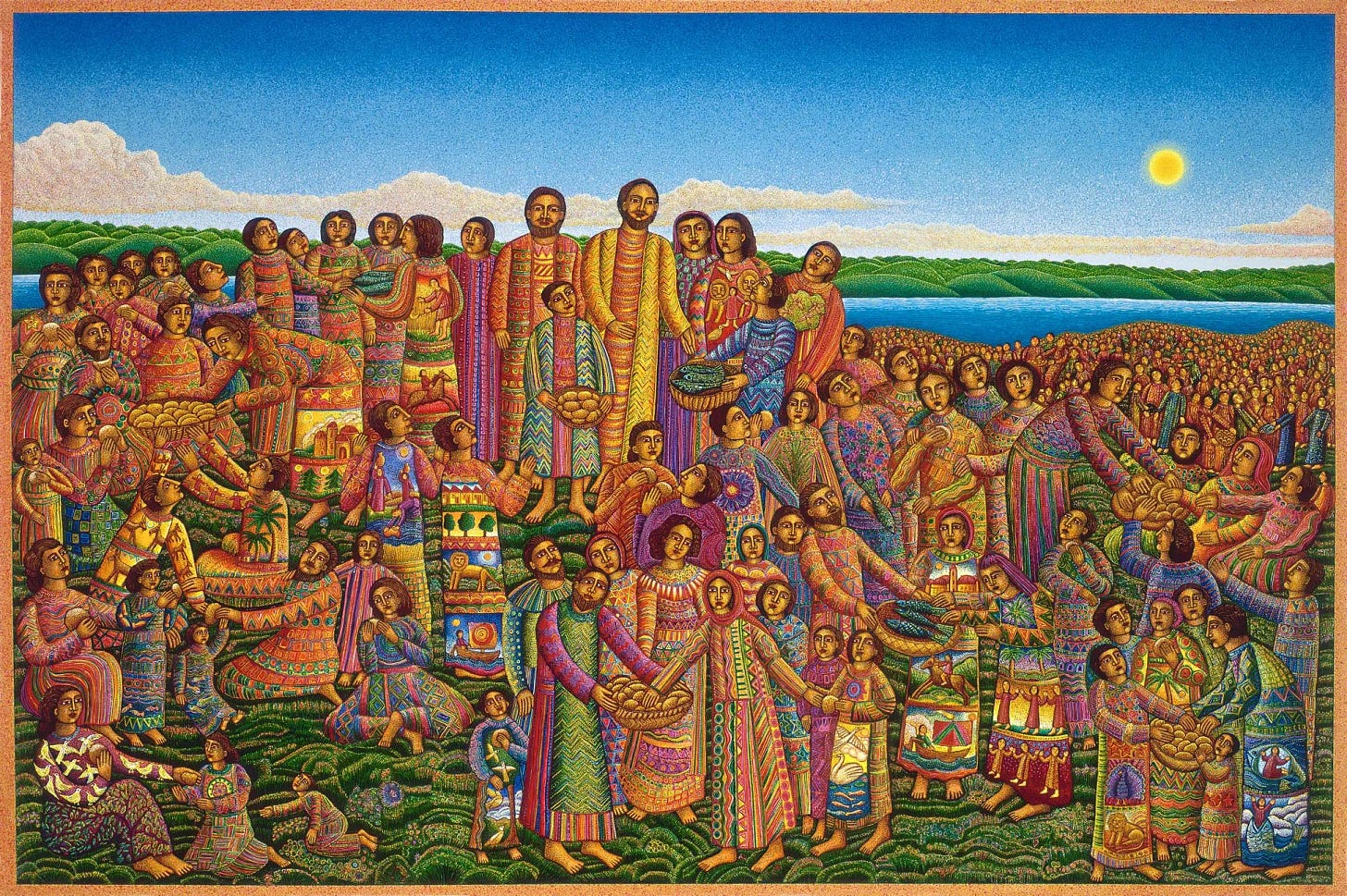

“Loaves and Fishes,” John August Swanson, 1986

Exodus Then

John 6 is the second of three Passovers in John. As explained last week, I’m covering Passover next in this series because of the seasonal order John uses in ch. 5-10: first Sabbath (a weekly celebration), then Passover in Spring, followed by Tabernacles in Fall, and lastly Dedication in Winter. This overarching structure shows that John was attending to the larger liturgical rhythm of Jewish life that his audience knew so well. That said, to see how John addresses the impact of trauma on Passover, we will start our exploration in ch. 6 and then connect it to other Passover narratives in John.

John gives the setting for ch. 6 on the other side of the Sea of Galilee/Tiberias (more on Tiberias in a minute). Then, almost in passing, he says “Now the Passover, a Jewish festival, was near” (6:4). As any 1st century Jewish child could tell you, Passover is a remembrance of the exodus. God gave this instruction to Israel from the first Passover observance:

“When your children ask you, ‘What does this ceremony mean to you?’ you are to reply, ‘It is the Passover sacrifice to the LORD, for he passed over the houses of the Israelites in Egypt when he struck the Egyptians, and he spared our homes.’” (Exodus 12:26-27 )

For Jewish Christian readers, this reference to Passover invites them to listen for other echoes of the exodus. And that’s just what John does. Like God testing Israel in the wilderness, Jesus asked Philip about buying bread for the people “to test him.” Like God miraculously providing the bread-like manna, Jesus miraculously turned five barley loaves and two fish into more than enough for 5,000+. Like God miraculously led Israel through the Red Sea, so Jesus miraculously led his disciples through the Sea of Tiberias (6:21). And many more echoes. Exodus is everywhere, once we know what we’re listening for.

Arthur Wright explains how this calls to mind Israel’s past:

“How does the Passover reference shape readers’ understanding of this passage? For one, the Passover reference introduces exodus imagery, which will be developed later in chapter 6 in reference to manna from heaven in Jesus’s “bread of life” discourse (vv. 25–58). Perhaps equally significantly, however, the Passover festival recalls the Israelites’ liberation and exodus from Egypt, a provocative, politically charged image for Jewish persons living under the domination of imperial Rome. The Passover observance and the ensuing festival of unleavened bread celebrated the liberation of God’s people and divine triumph over Egyptian power. This exodus imagery thus locates Jesus’s feeding of the multitude within the context of God’s actions to overcome imperial domination and to liberate God’s people.”2

Exodus Now

Now, that is the past reference and meaning of Passover.3 What about in the time of Jesus, or the community of John? I think Christians frequently provide the wrong answer to this question. For example, Doug Ponder:

“In view of all this [connection between John 6 and the exodus], it seems that John wants the reader to see the crossing of the Sea of Galilee as a symbolic fulfillment of the crossing of the Red Sea in the exodus/Passover narrative. But why? It is because John wants us to see Jesus as the greater Moses…Therefore, in John 6, Jesus is revealed as the One who brings about the new exodus, that is, the true liberation of God’s people from slavery to sin, the inevitability of death, and the just judgment of God. As the Passover Lamb (John 1:29) and the One who leads His people safely through dangerous waters (John 6:16–21), Jesus is true source of our deliverance.”

I wonder, would John agree with this statement, that the new exodus equals “the true liberation of God’s people from slavery to sin, the inevitability of death, and the just judgment of God”? There are clues in John 6 that more is going on here than rescue and liberation from sin (at least, one’s own personal sin). Ponder was right to attend to images and symbols of the exodus, but he missed images and symbols of empire. He writes that “in Scripture, the sea tends to symbolize sin, death, and judgment,” and thus, the “new exodus” through the Sea of Galilee/Tiberias symbolizes the same, rescue from sin, death, and judgment.

Interestingly, though, John is the only NT writer who refers to the Sea of Galilee as the Sea of Tiberias (6:1, 23; 21:1). As I wrote about here, I follow Arthur Wright’s explanation of this reference:

“By evoking the name Tiberius (v. 1 and again in 6:23 and 21:1), the author recalls the Roman occupation and dominance of the region. Unlike the feeding stories in the Synoptic Gospels, here in the Fourth Gospel, the reality of Roman imperial domination and rule are brought to the foreground of the narrative.”4

This is incredibly significant. Passover is about rescue from the empire of Egypt. The imperial presence of Rome, which saturated all of 1st century life in Judea, Samaria, and Asia Minor5, is highlighted by John. Which is strange, because there is nothing obviously Roman about John 6. It’s a Jewish story, through and through (more on that in a minute).

What isn’t as obvious about the Tiberias at first glance comes later in John 21, the last reference to Tiberias. In that narrative, there is a connection to Egypt and the sea as symbols of empire. In John 21:7 Peter “threw himself into the sea.” The first and last occurrence in the Bible of this language, of something being thrown into the sea, is applied to both Egypt (Exodus 15:1, 4, 19, 21) and Babylon/Rome (Revelation 18:21).6 This suggests deeper symbolic layers in John’s change of reference from Sea of Galilee (only 1x, 6:1) to Tiberias (2x, 6:1, 23).

The disciples were miraculously saved from the waters of the Tiberian Sea like Israel was saved from the waters of the Red Sea. Only, that doesn’t complete the comparison, because, for Israel, it wasn’t the sea that was dangerous. The real danger was the Egyptian empire. Is there a corresponding reality for the disciples in the boat or John’s audience sixty years later? Tiberias is the key clue, but I don’t think jumping to Rome is the right move (much as I commend Arthur Wright’s article on this passage). Instead, this symbol of imperial domination is set right alongside a religious festival. Rome isn’t in view, at least not directly. It’s the empire-like religious system centered in Jerusalem which Jesus, and John after him, are disconnecting from the festival and gift of Passover. To make the anti-imperial message abundantly clear, Jesus sneaks away to a mountain when he “realized that they were about to come and take him by force to make him king” (6:15). He is not about to fight empire with empire (cf John 18:10-11, 36).

Disconnecting Custom from Corruption

I said above that John 6 is a Jewish narrative through and through because of the repeated echoes from the exodus. But it’s not as Jewish as we might think. Notice what John says again in 6:4: “Now the Passover, a Jewish festival, was near.” Why describe this as a Jewish festival? That would be like calling Christmas a Christian holiday. We might do that in a secular context, but it would be strange while writing or talking to Christians. So, John is putting some distance between Passover and his Christian audience.

John had already done this in 2:13 when he called it “The Jewish Passover.” Again, strange. But what isn’t strange in ch. 2 is that Jesus goes up to Jerusalem specifically because of Passover (2:13). Similarly in 11:55, when “the Jewish Passover was near, many went up to Jerusalem from the country.” This is what faithful Jews do: they go to Jerusalem once a year for Passover.

The narratives in ch. 2 at the temple, as well as all of ch. 11-19, are oriented around the first and third of three passovers in John. The passover in ch. 6 is the second, in the middle, and noticeably different: Jesus intentionally stays away from Jerusalem. There is a logical connection between 6:4 and 5: “Now the Passover, a Jewish festival was near. So, or Therefore,” he stayed in that region and fed the people. What more can we say about this disconnection of Passover from Jerusalem?

Here’s Wright again, following two other John scholars:

“Tom Thatcher and Richard Horsley suggest that Jesus’s act of feeding is consequently and “pointedly in opposition to the official celebration [of Passover] in Jerusalem” where the Jewish ruling elites are allied with Roman imperial power. They celebrate the Passover festival in Jerusalem, while ironically partnering with their oppressors.”7

Thus, the Johannine Jesus

“presents an alternative to the Passover festival in Jerusalem. Rather than celebrating their liberation from Egypt at the elite-controlled Temple, these followers look to Jesus for a new vision of liberation.”8

Warren Carter, quoting another scholar, agrees:

“The Passover festival is again the setting [6:4]. But instead of making a pilgrimage to Jerusalem, Galileans gather with Jesus for what Allen Callahan calls ‘a counter-Passover: without money, without sacral slaughter and without the Jerusalem priesthood that oversees the exchange of the one for the other.’”9

But why would these followers look to Jesus for a new vision of liberation? We could take a line from Paul or the author to the Hebrews and say Jesus is the true and final fulfillment of the type/shadow of Passover. While that is true, it doesn’t say enough, because it ignores the traumatic context of John’s audience. So we must say more: they needed a new vision of Passover liberation because the religious tradition that celebrated Passover had itself become an oppressive system.

Spiritual Abuse and the New Exodus

Through the references to Passover, John has linked the narratives of the temple cleansing in ch. 2 and the new exodus narrative of ch. 6. So, readers are prepared to see Jesus’ disconnecting Passover from Jerusalem—and connecting it directly to himself—in light of the first Passover when he removed imperial corruption from the temple and connected the temple directly to himself.

Additionally, I believe John has drawn a comparison, albeit implicitly and symbolically, between Egypt, Rome, and Jerusalem. As the Israelites were rescued from Egyptian oppression, so this Christian community had been rescued from the oppression of a worldly, imperial religious system. There is one more exodus allusion that brings this out, namely, Israel wasn’t just liberated from Egypt, they were expelled.

Right after the first Passover, we read this in Ex 12:33: “And the Egyptians were forcing the people, to throw them out of the land quickly. For they said, “We are all dying!” (NETS). The word for “throw out” is the same word used twice in John 9:34-35, ekballō. There is near identical language in ch. 2 when Jesus “threw out” the religious marketers out of the temple.10

In ch. 9 when the healed man is expelled from the synagogue, John also uses ekballō, but we might expect John to put that differently. In 9:22 we see the first instance of the rare word aposynagōgos to describe those banned or put out of the synagogue. It seems that is what happened to the healed blind man in 9:34. Why wouldn’t John use aposynagōgos again?

As with all of John’s subtle choices of word, I think it’s intentional: repeatedly in Exodus, Pharao and the Egyptians ekballoed, threw out, Moses and the Israelites. For example, when God predicts the last plague, which was connected to Passover:

“Then the Lord said to Moses, “Still one plague I will bring upon Pharao and upon Egypt, and after these things he will send you away from here. Now whenever he sends you away, with everything he will expel you with expulsion” (Ex 11:1, NETS).

Notice how that last line is emphasized. It’s ekballō twice, first as a verb, then as a noun: ekbalei hymas ekbolē. It’s very similar to the twice-repeated phrase in John 9:34 and 35, exebalon auton exō, literally, “They threw him out out.” Furthermore, the Exodus narrative repeats the ekballō throwing out of the Israelites by Egypt twice in direct reference to the Passover in 12:33 and 39.

This makes Jesus words in 6:37 all the more significant: “Everyone the Father gives me will come to me, and the one who comes to me I will never cast out.” There’s that phrase again, only negated: ou mē ekbalō exō. “I will never cast out out.” In other words, what Egypt did to Israel, and what the Ioudaioi did to these Christians, Jesus will never, ever do.

Thus, the Jewish remembrance of Passover includes the remembrance of being thrown out by an oppressive empire. Ironically, as Arthur Wright observes, the Jewish religious leaders have themselves become allied with empire through their interest in Passover:

“[I]t is ironic that [the Jewish authorities] wish to eat the Passover meal [pascha, John 18:28]. The Passover meal symbolically recalls the liberation of the Jewish people from oppression under the domination of a foreign power: Egypt. The Jewish authorities wish to participate in this symbolic remembrance of victory over a foreign power, but by the end of the Roman proceedings [in Jesus’ trial] they end up pledging exclusive loyalty to the emperor of a new, oppressive foreign power: Rome.”11

Subtly, but surely, John is inviting his audience to transfer, not just the spiritual reality, but also the physical, embodied systemic reality of the exodus to their excommunication from Jewish community and social/religious life.

Eucharistic Liberation

If I had more time and space, I would trace this thread of liberation from religious oppression to the rest of John 6 and the bread of life discourse. I agree with scholars who see eucharistic symbolism in Jesus’ invitation to “eat the flesh of the Son of Man and drink his blood” (6:53). Indeed, Jesus “gave thanks” before distributing the bread and fish (6:11, eucharisteō), the same word used in the Synoptics and Paul for the Lord’s Supper (Matt 26:27; Mark 14:23; Luke 22:17; 1 Cor 11:24). With more space, here’s what I would unpack: because Passover became tainted with trauma, because this core Jewish festival had become corrupted through collusion with imperial policies, Jesus took that ritual and connected it, not only to himself, but also to the rescue he provided from toxic religion.12

In a word, Eucharist (or the Lord’s Supper, or Communion) is about liberation in the fullest biblical sense: freedom from sin, personal and systemic. This kind of liturgy, properly shaped by this Johannine pastoral theology, would be a balm to those wounded by oppressive religious leaders and churches.13

Quote from Wes Howard-Brook

“The fact that the members of this Jewish Galilean crowd [in John 6] choose to pursue Jesus in Galilee rather than go to Jerusalem for the feast is powerful evidence of their disaffection from the dominant Judean ethos. Might Jesus the healer be the one to liberate them from the oppression the Judean Temple-state has imposed?”14

Question

Have you ever observed the Lord’s Supper with reference to liberation from the sin of others and not just your own personal sin? If not, why not? If you have, what was your experience?

1 Mary Coloe, “Session 7: Receiving the Bread of Life,” at Broken Bay Bible Conference, Gospel of John: Joy Made Complete, September 13, 2014.

2 Arthur Wright, “The emperor’s new loaves: Scarcity and abundance in John 6:1–15 and 21:1–14,” Review & Expositor, 119, no. 3–4 (2022), 411-412.

3 Another OT image I don’t have space to cover is Jesus as the paschal lamb: “Symbolically and ironically, the Johannine Jesus becomes the sacrificial Passover lamb, a theologically loaded image. The Passover festival recalled the Israelites’ liberation and exodus from Egypt, which would have been a provocative, politically charged image for Jewish persons living under the domination of imperial rome” (Arthur Wright Jr., The Governor and the King: Irony, Hidden Transcripts, and Negotiating Empire in the Fourth Gospel, 124.

4 Wright, “The emperor’s new loaves,” 411.

5 Possible locations of the Johannine community.

6 It would take too much time to look at all of the evidence of this biblical pattern, but here are the relevant passages: Ex 10:19; 14:27; 15:1, 4, 19, 21; Ezek 27:27; Jer 51:42; Jon 1:5, 12, 15; Mic 7:19; Zec 9:4; Mk 9:42; Lk 17:2; Acts 27:38; Rev 8:8; 12:9; 18:21; 19:20; 20:10, 14-15.

7 Wright, “The emperor’s new loaves,” 412.

8 Wright, “The emperor’s new loaves,” 413.

9 Warren Carter, John and Empire: Initial Explorations (New York: T&T Clark, 2008), 163.

10 Given that John 2 is set in a temple context, there is probably an allusion to Genesis 3:24 when, according to the Septuagint, God “drove Adam out” of the garden-temple, using the same word, ekballō.

11 Wright, The Governor and the King, 125.

12 Chris Blumhofer notes the wording of the Passover Haggadah which originates from around the same time as John: “This is the bread of oppression, which our fathers ate in the land of Egypt; everyone who hungers may come and eat; everyone who is needy may come and celebrate the Passover feast.” See Blumhofer, “The Gospel of John and the Future of Israel,” PhD Dissertation (Durham, NC: Duke University, 2017), 209.

13 Indeed, we could trace this Eucharist / New Exodus theme through the study in Part 1 on Sabbath and the end result of the disciples being liberated from fear of their religious oppressors. According to Bruno Barnhart, the locked doors in the resurrection scenes in John 20:19-29 echoes, in part, the Passover: “The closed place recalls the houses where the Israelites sheltered themselves behind closed doors on the Passover night (Ex 12:22-27).” (The Good Wine, 251). This implies that, as the Israelites were liberated from the Egyptians, so the disciples were liberated from the Ioudaioi.

14 Wes Howard-Brook, Becoming Children of God: John’s Gospel and Radical Discipleship (Maryknoll, NY: Orbis Books, 1994),143.